AN ESSAY ON THE SILMARILLION IN TWO PARTS

Part One: A commentary on Tolkien's 1951 letter on The Silmarillion

AN ESSAY ON THE SILMARILLION IN TWO PARTS

Part One: A commentary on Tolkien's 1951 letter on The Silmarillion

Previous pages have provided some of the many questions and allusions that The Silmarillion proposes, but how does one approach the text deductively? According to the Second Edition's Preface and in Christopher Tolkien's words, his father urged LOTR and The Silmarillion "...be published 'in conjunction or in connexion' as one long Saga of the Jewels and the Rings." (page ix). Allen and Unwin were reluctant given the many dozens of proper names, synonyms and complex genealogies that make comprehension a challenge, and Tolkien himself admitted the book was difficult. Could an enthusiastic audience be found?

In 1951, Tolkien wrote to Milton Waldman, (Collins) explaining his intentions in wanting both texts publishes simultaneously, and that letter introduces the second edition of the Del Rey's paperback publication. (See also Tolkien's Letters, 131. Therein, Christopher outlines the publication difficulties). Perhaps Tolkien himself knew how daunting his persuasions would have to be; in the first paragraph, he notes to Waldman, "I shall inflict some of this on you." (xiii)

The letter, of some ten thousand words, must therefore begin our discussion. In his Prefatory remarks, Tolkien argues that,

-his characters exist for the languages he was in the progress of creating (xiii). Philology is his first love, and myth supersedes allegory.

-England suffers from a lack of myths in the vernacular, especially those with the Christian perspective needed to sustain the moral perspectives he deemed essential for a nation's surivival. (xiv). For more, see his Fairy Tale Essay. and The Mythopoeia.

-the power of the elves rests in their sub-creative talent memorialized in their art; they wish immortality; not domination.

The Silmarillion and Lord of the Rings:

The focus of the post-creation myth, in which the 'gods'-the Ainur / Valar- see but a part of the whole as they subcreate is the Elvish immortality archetype, while the followers, men, are given mortality. Ironically and through the perversions of Melkor, each envies Illuvatar's gift to the other race. Tolkien uses 'doom', but a fortunate one given his Roman Catholic orientation, allowing for the recovery, escape and consolation as outlined in the Fairy Tale Essay.

Symbolically, Tolkien describes the Silmarils (xix) as made ultimately from the light of Valinor and "made visible in the Two Trees of Silver and Gold," (xix), hence divinely ordained. Tolkien's sin, as with Rousseau in one of few areas besides their mutual love of nature in which they might agree, is greed, and possessiveness, for Melkor and Feanor both lusted after the Silmarils (Chapter VII). Such unbridled desire prefigures the latter's terrible oath, the defiance of the Valar and most tragically, the kinslaying. Interestingly, Mandos' warning of "Tears unnumbered ye shall shed" is echoed later in the Fifth Battle of Beleriand, the Nirnaeth Arnoediad or "Unnumbered Tears," (Chapters 9 and 20). Tolkien (xx) calls the oath "terrible and blasphemous." Feanor's actions decimate Middle Earth which is geographically altered, separating it from Valinor:

|

|

||||||

|

Arda before

|

Arda After

|

||||||

The first age ends, and the cosmos is not the same. Estrangement from God requires atonement (Campbell reminds us of the need for at-one-ment), which occurs through the intervention of Messianic figures provides.

Tolkien's later stories interweave men in the Elvish narrative, and often conflict ensues. He expresses a point I often have made in my classes, that the 'Elvish' doom of immortality is but part of our human nature (footnote xxi), and given Tolkien's own aborted genealogy and the horrors of World War I, one should not be surprised.

The analysis of the Story of Beren and Luthien, the Elfmaiden, (xxi) should, along with the entire letter, be examined in the original very carefully. In addition to being the most poignantly autobiographical, the tale dramatizes a theme he considers significant, that the "seemingly unknown and weak" (xxi) will accomplish what all the armies cannot: a silmaril is recovered, and a mortal and immortal marry, and Beren and Luthien will have to make a choice. Sadness follows.

Another of Tolkien's archetypes, the quest, is the voyage of Earendil, the Wanderer (xxi), a Christ-like figure- whose descendents will figure predominately in LOTR, illustrating that Out of what appears to be evil comes great good, . His 'title' of 'wanderer' recalls the Anglo-Saxon poem of the same name. Context is terribly important here. We know of a prior journey for the wrong reasons that lead to disaster; Earendil's leads to salvation. Feanor lusts; Earendil sacrifices: "...that peril I will take on myself alone, for the sake of the Two Kindreds" (Chapter 24). Here, the quest defines what Tolkien's heroes desire; they come to servel not to dominate or control.

Tolkien's second age, referred to as dark (xxii) recalls Jung's shadow archetype. The elves have been exiled from Valinor (heaven) to Tol Eressa:

Sauron of course, hoping to divide and conquer-men vs. elves / elves vs. dwarves / men and elves vs. God, will do much to sow discord in the Trilogy. Here, hubris flourishes, and Numenor is humbled.

Hoping to convince his publishers of the need for this cosmological frame, Tolkien admonishes (xxii), not to ignore the backstory, amazingly even more complex now than in 1951, since Christopher has published more of his father's working notes.

In philosophical terms, the elves are nominalists and realists: they want the bliss of Valinor and the beauty of Middle-Earth, a dilemma involving the relationship between form and substance, mind and matter that had been plaguing philosophers since the pre-Socratics. Thus, on Middle Earth, Elves 'fade' (xxiv). Sauron, observing their dilemma offered the rings as a means of making "...Western Middle-earth as beautiful as Valinor. It was really a veiled attack on the gods, an incitement to try and make a separate independent paradise." (xxiv). Tolkien adds that such power belongs only to the gods. It's use otherwise is sinister.

One of the cruxes of Greek philosophy was the relationship between change and permanence: Heraclitus and Parmenides. For Tolkien, that meant mortality and immortality or eventual union with God. I believe he wrote to validate that longing, and that he felt divinely inspired to do so. Yet, he was alive on earth, and no doubt yearned for the time needed to fulfill the demands of career, his art, and family. Importantly, Tolkien defines what the ring accomplishes as 'magic' (xxv), but not in the sublime sense as discussed in the Fairy Tale Essay.

Middle Earth then acquires a kind of siege mentality--Rivendell, Lothlorien etc. are fading vestiges of what once was in the Blessed Realm. Yet Sauron, although potent and apparently invincible with the ring, does not triumph. Evil, as Henry James believed, was insolent and strong, while the good often appeared impotent, and Tolkien would agree, but he also believes (xxvi-xxvii) that evil defeats itself. The very power the ring appears to bestow can turn on its former wearer if someone else has it, and most vitally for LOTR, its destruction in Mt. Doom would end Sauron's presence. Ironically, Tolkien notes how he fatally miscalculates. Would Hitler have renounced nuclear technology? In the LOTR, the debate over the ring's use centers on Boromir. What does he and his father not understand?

Tolkien continues to discuss Numenor and the corruption of men by Sauron. Whereas Eru intended it as a gift, mortality becomes a curse: "Reward on earth is more dangerous than punishment." (xxvii). The wisdom of Eru is ignored. Men are not permitted to sail to Eressea (the Elvish island). Tolkien's reason is essential to LOTR. For men to have immortality on earth would be a violation of the Divine order. To cling to what he have on earth to "ensure" immortality would engender greed, but men do not listen. Rebellion is in the wind. Tolkien provides three stages to their decline (xxvii-xxix):

Tolkien concludes his letter by noting that the second age ends with Elendil and his sons, Isildur and Anarion, who do not participate in the rebellion, flee the destruction (Tolkien calls him "Noachian" (xxxi) and establish Arnor and Gondor in Middle-Earth. The Second Age ends with the Last Alliance with what Tolkien calls "...one disastrous mistake." (xxxi), the taking of the ring by Isildur. The consequences of that decision define the Trilogy.

Part II suggests ideas from The Silmarillion that have special

|relevance to Lord of the Rings. The outline proceeds

chronologically: each Silmarillion commentary is

followed by relevant LOTR comparisons.

The Silmarillion

The Ainur only comprehend part of what Illuvatar intends; sub-creation is delegated. . When Melkor introduces discord, Illuvatar cautions, "...no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me." Tolkien's cosmology mandates a theocentric perspective that will bring good out of evil, but not before considerable anguish for the races of Middle Earth.

The Lord of the Rings

When the company splits, and especially after Gandalf "dies," each surviving member is not aware of how their actions ultimately help Frodo and Sam. Aragorn knows,"We shall all be scattered and lost," but Frodo tells Sam, "It is plain that we were meant to go together...may the others find a safe road. Strider will look after them." (Breaking of the Fellowship).

The Silmarillion

The Ainur behold creation in a vision that is yet to be actualized. When done, each 'god' plays a role that collectively realizes Illuvatar's plan, even Melkor discord serves the divine purpose. Tolkien argues that the right to be free also implies the right to make bad choices. We read that "...it came into the heart of Melkor to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of Illuvatar." Interweaving recalls the classical fates; we are destined for the "Blessed Realm," but how becomes a matter of the potentials we choose to actualize.

The Lord of the Rings

In The Riders of Rohan, Aragorn rebukes Gimli's questioning of Galadriel's gift of light to Frodo: "Ours is but a small matter in the great deeds of this time," he cautions. Galadriel herself, admonishes Frodo as he views the mirror: "Remember that the mirror shows many things, and not all have yet come to pass. Some never come unless those that behold the visions turn away from their path to prevent them. The Mirror is dangerous as a guide of deeds." (The Mirror of Galadriel). Perspective is important. Galadriel remembers the kinslaying, was eager to depart to Middle Earth, but did not take Feanor's oath.

The Silmarillion

Obviously in The Silmarillion Feanor and Aule, although loving crafts, are sharply contrasted. Feanor ("spirit of fire") lusts after the great jewels, and refuses to share them with Yavanna to heal the trees. (Of the Flight of the Noldor) Aule too seems to lust, but after creating the Dwarves without permission, recants: "And in my impatience have fallen into folly." (Of Aule and Yavanna). Thus the Dwarves are spared. Later, Isildur of Gondor, at the Last Alliance, had a chance to destroy the ring, but of course did not: it became his 'precious.' -he "took it for his own" (Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age). To be moral in Tolkien's universe is to renounce.

The Lord of the Rings

Obviously in LOTR, Boromir's lust for the ring proves his undoing. At the Council of Elrond, "Boromir's eyes glinted as he gazed at the golden thing." Readers of Beowulf should recall the allusion. Contrast Faramir's words, in The Window on the West, "If it [the ring ] were a thing that gave advantage in battle, I can well believe that Boromir, the proud and fearless, often rash, ever anxious for the victory of Minas Tirith (and his own glory therein), might desire such a thing and be allured by it...I would not take this thing, if it lay by the highway. Not were Minas Tirith falling in ruin and I alone could save her, so, using the weapon of the Dark Lord for her good and my glory." How well he knows his brother, and how little his father knows him.

The Silmarillion

Yavanna's love of nature, another self-evident archetype, often focuses on trees: "Would that the trees might speak on behalf of all things that have roots," she laments, "and punish those that wrong them."

The Lord of the Rings

The Ents of course actualize that desire as Isengard finds out to its regret. Readers who complained that the Entmoot took entirely too long miss Tolkien's profound love of trees. Jackson's treatment of their uprooting at Isengard graphically portrays the horror of their 'murder,' which eventually move them to action.

The Silmarillion

The Elves awaken in darkness, but see the stars: "...they rose from the sleep of Illuvatar; and while they dwell yet silent by Cuivienen, there eyes beheld first of all things the stars of heaven. Therefore they have ever loved the starlight, and have revered Varda [Elbereth] Elentari above all the Valar." By contrast, Melkor and Ungoliant bring forth unlight in a Dracula- like fashion.

The Lord of the Ring

In The Land of Shadow with the rotting stench of Mordor and Mt. Doom about Sam and Frodo, Tolkien writes: "There peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart...and hope returned to him...there was light and beauty for ever beyond its [Mordor's] reach." And earlier, in The Choices of Master Samwise, Frodo's friend sings to Elbereth and uses Galadriel's gift to repel Shelob, descendent of Ungoliant which fouled Arda.

The Silmarillion

I ask in the chapter questions for The Silmarillion if Feanor is tragic. He parallels in some respects a major figure in LOTR: "Feanor was a master of words, and his tongue had great power over hearts when he would use it." (Of the Flight of the Noldor), and we know the consequences of the oath that followed. Predicated on a lust for the jewels, Feanor's actions precipitate the kinslaying and the "unnumbered tears" warning of the Valar.

The Lord of the Rings

Obviously as a philologist, Tolkien knew the power of language: he created characters for his words, and in the 1930's Hitler's oratory mesmerized much of the world. In LOTR, who speaks with a enchanter's voice?... "Suddenly another voice spoke, low and melodious, its very sound an enchantment...Mostly they remembered only that it was a delight to hear the voices speaking, all that it said seemed wise and reasonable." (The Voice of_____). The language is complex. We know from the creation myth the importance of melodious, even after and to a degree because of Melkor. In the Fairy Tale Essay, Tolkien speaks of the power of art to enchant. Virtue and vice, recalling the Friar in Romeo and Juliet, apparently can mingle as they do here in the creation myth. Yet a few sentences later in the same chapter, some perceive what they hear as a "juggler's trick. " Such should remind us again of another word Tolkien uses in both its conventional and, for us, non-conventional sense: MAGIC. What are the connotations? Recall as well Keat's Eve of St. Agnes' use of hoodwinked.

The Silmarillion

The making of the sun and the moon is one of Tolkien's most beautiful acts of subcreation, but their existence occasions Morgoth's hatred. In attacking them, he sows ironically his own demise: "...for as he grew in malice, and sent forth from himself the evil that he conceived in lies and creatures of wickedness, his might passed into them and was dispersed, and he himself became ever more bound to the earth, unwilling to issue from his dark strongholds." (Of the Sun and Moon). As a Catholic, Tolkien understood earth as just a prelude to union with God if our lives so merited. Too much attachment to the material disrupts our quest. POWER and LUST rarely if ever find positive expression in Tolkien's art.

The Lord of the Rings

Evil destroys itself. In the letter analyzed above, Tolkien notes the power of the ring to enslave; to bind one to the material and as just described, he believed earth to be but the beginning of man's quest for immortality that can only be perfectly realized by union with God in the afterlife. What is Sauron's error in this regard, and how does it mime Morgoth's? What does he fail to anticipate? In the Mount Doom chapter, study Tolkien's description of what happens geographically immediately after the destruction of the ring.

The Silmarillion

Two contrasting archetypes, immortality and mortality define The Silmarillion. Each is Illuvatar's gift to elves and men respectively, but ironically and with perverted joy, Melkor encourages each race to yearn for what the other was given: "But Melkor has cast his shadow upon it, and brought forth evil out of good and fear out of hope. " (Of the Beginning of Days). In Of Men, it is written, "Immortal were the Elves, and their wisdom waxed from age to age...But men were more frail, more easily slain by weapons or mischance, and less easily healed; subject to sickness and many ills; and they grew old and died." Throughout The Silmarillion, men more often seem most susceptible to material enticements.

The Lord of the Rings

At the Council, Elrond reminds all that he had seen the three ages of Middle Earth including the Last Alliance. At Dagorlad, he was Gil-galad's (the son of Fingon, and nephew of Feanor) herald. Frodo, as perhaps many of Tolkien's readers, is stunned to know his incredible age, but while reflecting, one senses his weariness: "I have seen three ages in the West of the world, and many defeats, and many fruitless victories." Men, however, want this. Recall Tolkien's description of Theoden: "Upon it [the throne] sat a man so bent with age that he seemed almost a Dwarf." (The King of the Golden Hall); yet with some assistance, he finds courage. However, Denethor does not: " 'Pride and despair!" he cried....The West has failed. It is time for all to depart who would not be slaves." (The Pyre of Denethor). In this same chapter, Gandalf notes that "Darkness is passing...but it still lies heavy on this City." Illuvatar would not bestow evil; but he does allow its misuse. At best he guides and prophecies when warning Feanor.

The Silmarillion

The daughter of Finarfin, Feanor's half-brother, Galadriel can trace her ancestry back to First Age events including the kinslaying. Interestingly, Foster's Concordance says little of her involvement, but in The Silmarillion (Of the Flight of the Noldor), provides what she does and does not do. Although supporting the return to Middle Earth, "...the words of Feanor concerning Middle Earth had kindled in her heart, for she yearned to see the wide unguarded lands and to rule there a realm at her own will, " she did NOT swear his oath. As recounted in Of the Noldor in Beleriand, she is deeply troubled by the oath and the crime, but believes "...hope may still seem bright." She seems to find some merit in Feanor's action, but when Melian, Luthien's mother, speaks of "evil there," she replies, "Maybe...but not of me."

The Lord of the Rings

In LOTR, Galadriel's assistance to the company with her gifts, advice and the mirror, proves invaluable. How does her past influence her guidance? In the Mirror chapter, her first words recall the sorrows she had witnessed, but reiterates that hope has yet to fade. Her perspective supports Tolkien's belief that although tears may be unnumbered, one must never despair. Yet, she cautions, her accumulated wisdom cannot determine choice, but it does offer perspectives. For the present, "...your quest stands upon the edge of a knife. Stray but a little and it will fail to the ruin of all. Yet hope remains while the company is true." What does true mean? In the Riders of Rohan, when asked the same question, Aragorn defines right action when asked by Eomer how one judges in times of strife: "As he ever has judged...Good and ill have not changed since yesteryear; nor are they one thing among Elves and Dwarves an another among Men. It is a man's part to discern them as much in the Golden Wood as in his own house." Tolkien uses the mirror to dramatize the above. We know it offers potentials, but it "...is dangerous as a guide of deeds." Her experience-derived wisdom mandates she renounce the ring even if appearing successfully expedient. In contrast, who disputes Galadriel's experience?

The Silmarillion

Morgoth, in Of the Coming of Men into the West, fears the arrival of men, but as with most dictators, he knows how to find an exploit a weakness, sensing an exploitable darkness: divide and conquer, for men potentially have the power to destroy the natural world that is most dear to Elves. Yet Melian prophecies that one man will come about whom legends and song will be told and sung for ages to come. Who? Human mortality indeed seems a curse here; they doubt the threat Melkor poses as they have not seen direct evidence of his dominion. Significantly for later events, Elves and Men eventually live apart. Tolkien may be arguing that immortality and mortality will not always find easy accommodation, as events in LOTR dramatize.

The Lord of the Rings

Recalling what Tolkien believes about legends, the Mythopoeia provides the subtext the LOTR dramatizes. For example, in The Riders of Rohan, Aragorn himself, were it not for Celeborn, would have doubted the fable told of Ents. In that same chapter, one of Eomer's riders scoffs at the idea of Hobbits even existing calling them, "...only a little people in old songs and chidren's tales...Do we walk in legends or on the green earth...?" Aragorn again provides the answer, "A man may do both...For not we but those who come after will make the legends of our time." In The Road to Isengard, Theoden, also speaking of Ents, notes, "Out of the shadows of legend I begin a little to understand the marvel of the trees...We cared little for what lay beyond the borders of our land. Songs we have that tell of these things...And now the songs have come down among us...and walk visible under the sun." One is reminded of Jesus' words to Thomas after the resurrection when he demanded empirical verification before believing.

The Silmarillion

Tolkien's hatred of technology's abuses-Morgoth's mace: Grond-echoes through The Silmarillion and LOTR. In Of the Ruin of Beleriand, Tolkien recounts Dagor Bragollach (The fourth battle of Beleriand--sudden flame) during which Morgoth fatally wounds Fingolfin, half-brother of Feanor. Tolkien's repudiation of Anglo-Saxon hubris finds expression in Fingolfin's clash with Feanor: "King and father, wilt thou not restrain the pride of our brother, Curufinwe, [Feanor] who is called the Spirit of Fire, all too truly?" Tragically, though, the "unnumbered tears" prophecy must be fulfilled. Perhaps this is Tolkien's way of dramatizing his conservative, orthodox Roman Catholic philosophy and morality. Also of importance in Of the Ruin of Beleriand is the appearance of Sauron, described as, "...a sorcerer of dreadful power, master of shadows, and of phantoms, foul in wisdom, cruel in strength, misshaping what he touched, twisting what he ruled, lord of werewolves; his dominion was torment." An infomative parallel is Milton's Satan, in Paradise Lost, especially his character in Book IV's soliloquy and the temptation scene in IX.

The Lord of the Rings

In Pelennor Fields, there are some parallels: Merry, the little Hobbit, assists Eowyn in the slaying of the Lord of the Nazgul, but Theoden is fatally wounded. Unlike Denethor, he responds to Gandalf's counseling by repudiating Wormtongue's "whisperings" of despair. Both Fingolfin and Theoden ultimately sacrifice their lives for a greater good by accepting Tolkien's premise that despair must never replace faith in an omnipotent providence that brings good out of evil, but sometimes at a tremendous price. Grond of course appears in LOTR as the monstrous battering ram used to assault Minas Tirith.

The Silmarillion

Of spiritual significance, Hurin notes in Of the Ruin of Beleriand, that "...the time is short and our hope and strength soon wither." Valinor yet "was hidden," and suffering seems unabated.

The Lord of the Rings

The problem of evil in a providential universe seems perplexing. In LOTR, evil, as the Nazi menace of the 1930's, seems invincible; the good often appearing incapable of overcoming it. Yet the scheme of LOTR echoes Jesus' admonition: "Oh Ye of little faith." The Hobbits were Tolkien's tribute to his World War I comrades, who won the peace with their lives.

The Silmarillion

Beren and Luthien has been discussed elsewhere on this site. Since their union seemed to echo Tolkien's marriage, one is tempted to associate the myth with Aragorn and Arwen. Specifically, Thingol demands a Silmaril as the price for Beren's union, she enters a man's world in battle, and given the choice by Manwe of immortality or mortality, chooses the latter, "This doom [mortality] she chose, foresaking the Blessed Realm..." In so doing, she dwells in Middle Earth, "...but without the certitude of life or joy." We might add pro tem, for in the scheme of things, their descends will help to save Middle Earth. Would we need faith were it not for uncertainty, for faith does not need to thrive in certitude.

The Lord of the Rings

In LOTR, would the Silmaril be Tolkien's career? We know that although happily married, he prioritized: his profession did not admit women, and it was tacitly understood that intellectual pursuits were not really discussed with them . But like Eowyn, Luthien "...took mastery of the isle...[she] stood upon the bridge, and declared her power." She saves Beren, chooses mortality and perhaps "lived happily ever after?" In LOTR, another parallel might be Eowyn who also, like Luthien, enters a male dominated world to join in battle. In The Steward and the King, Tolkien writes, "And Aragron...wedded Arwen Undomiel in the City of the Kings, upon the day of Midsummer, and the tale of their long waitings and labours was come to fulfillment."

The Silmarillion

The fifth Battle of Bereliand, Nirnaeth Arnoediad (unnumbered tears) brings the prophecy to tragic fulfillment. Mandos' warning speaks of betrayal which does occur even against the union of Maehdros, who forgot not the oath. He too lusted after the Silmarils: "...the words of the sons of Feanor were proud and threatening." Melkor's design (as presented in Of the Ruins of Beleriand,) exploited men's lust for treasure, thus sundering them from the elves. In the last battle, "...the sons of Ulfang went over suddenly to Morgoth." Ironically however, the received not what was promised. Evil never delivers the happiness it promises, but Melkor appears victorious: "Great was the triumph of Morgoth, and his design was accomplished in a manner after his own heart...From that day the hearts of the elves were estranged from Men, save only those of the Three Houses of the Edain." [the future Dunedain]. For Tolkien, evil prospers from generation to generation, and not without great sacrifice does good triumph, but not completely on earth. Thus Valinor and Middle Earth are estranged.

The Lord of the Rings

Tolkien's perspective on the spread of evil may at least be partly engendered by the diplomatic, political and military crises that gripped Europe between the world wars. France and England, so easily seduced by Hitler's promises, seemed ill prepared to stand firm. In Middle Earth, Saruman's oratorical skills likewise enchants, but evil does mar evil. Jackson's film compresses one of the best examples since the movie cuts The Scouring of the Shire. At the chapter's conclusion, we know what Wormtongue does to Saruman, and then what befalls him, but what saves the Hobbits and the Shire is their innate goodness, in Gandalf's words, pity. Throughout the LOTR, evil indeed seems invincible as did Hitler. Interestingly, Saruman vanishes into a mist of nothingness as did Dracula. The ending of Stoker's novel suggests he will return, as will Sauron in a different form. In The Silmarillion, vampire imagery is frequently employed as in the Beren and Luthien chapter.

The Silmarillion

The tragic tale of Turin narrated in Of Turin Turambar reminds us of Boromir. Both are heroic, but suffer from hubris, the flaw Tolkien hoped Christianity would modify in Anglo-Saxon culture. Turin's (self-imposed) exile as an outlaw, recalling The Wanderer, leads to the accidental death of his elf-friend, Beleg. Two motifs, revenge and the dragon archetype further define an Anglo-Saxon perspective. Paralleling Gardner's personification of the dragon in Grendel, Tolkien's worm Glaurung speaks, condemning Turin and perhaps aspects of Anglo-Saxon culture: "Evil have been all thy ways, son of Hurin. Thankless fostering, outlaw, slayer of thy friend...captain foolhardy, and deserter of thy kin." If evil has its own kind of (perverted) wisdom, and dragons, as in Beowulf, personify greed, in what sense is Turin foolhardy? Gwindor notes, "The doom lies in yourself." Perhaps the dragon, like Thersites in The Iliad, personifies an ugly truth, for in the Monsters and Critics Essay, Tolkien laments that the tragedy of being an Anglo-Saxon was just to be alive at the time. Turambar means, "Master of Doom." In what sense is Turin responsible for the 'incestuous' union with 'Nienor'? From a psycho-moral perspective, does that revelation from Glaurung personify Turin's fate? Is he the curse that destroys his family? Thus at the tale's conclusion, Turin slays the beast, but takes his own life, a victim of his hubris.

The Lord of the Rings

Tolkien of course did not condemn Anglo-Saxon culture unilaterally as his Anglo-Saxon characterizations of Boromir, Faramir, Denethor and Theoden illustrate. Boromir's pragmatism, his eyes "... glinted as he gazed at the golden thing," is dramatized when he attempts to seize Frodo's ring. Yet after repenting, Aragorn bestows his blessing: "You have conquered. Few have gained such a victory. Be at Peace." (The Departure of Boromir). Faramir is more complex having to bear the animosity of his father, perhaps the most Turin-like character, given the manner of his death. Tragically, when Denethor confronts his son regarding Boromir's death, he makes his preference clear: "Do you wish then," said Faramir, "that our places had been exchanged." "Yes, I wish that indeed...for Boromir was loyal to me and no wizard's pupil...He would have brought me a mighty gift." Therein lies Denethor's flaw, one so severe that he will end his life in the manner of Turin. Gandalf's remark that he is "proud and subtle" (Minas Tirith) reminds us of Turin. Tolkien's point of view, however, suggests a different perspective, "Here was one with an air of high nobility such as Aragorn at times revealed, less high perhaps..." (The Siege of Gondor). As noted above, Theoden accepts by contrast the 'wizard's' wisdom and is redeemed. Undoubtedly, Aragorn synthesizes the best an Anglo-Saxon CHRISTIAN represents.

The Silmarillion

Morgoth hopes to spread evil by 'dividing and conquering,' Sowing enmity between the first and second children, of Illuvatar, Mim and Beleg for example, reverberates through The Silmarillion and LOTR. In Of The Ruins of Doraith, lust, deception, jealousy and revenge precipitate tragedy; more 'unnumbered tears.' . Specifically, Nauglamir, the great Dwarf necklace given to Thingol ironically as 'thanks' for 'protecting' his family, exerts its 'ring-like' influence . Like the ring, visions of ownership, especially with a Silmaril cannot seemingly be resisted. The enmity between Elves and Dwarves flairs as desire trumps moderation. Thingol is killed, and Melian, a Maia, vanishes from Middle Earth exposing Doraith to ruin. Even Beren and Luthien cannot remain uninvolved, for in combat, Beren recovers the Silmaril and necklace, now warn by Luthien, for their son and heir, Dior. Mandos' prophecy continues to unfold when, for the second time, Elf slays Elf. With Melian's protection gone, The great kingdom of Doraith falls.

The Lord of the Rings

In so many obvious ways, these Silmarillion chapters preface LOTR. The ring is beautiful, but as Shakespeare writes, "All that glitters is not gold," and here, that which does glitter is dangerous. One can morally rank the Trilogy characters by their attitude toward the ring. Those who refuse (Aragorn, Galadriel, Faramir for example) triumph, while those who lust for it do not (Denethor). Probably the most tragic figure in LOTR in Gollum whose craving for his 'preciousss' becomes an addiction. Frodo's quest, however, unlike Feanor's and Melkor's is to return something, so an anti-quest. Frodo himself seems to understand the distinction. He tells Sam after Mt. Doom, "But do you remember Gandalf's words: Even Gollum may have something yet to do, but for him Sam, I could not have destroyed the Ring. The Quest would have been in vein...So let us forgive him!" For those who argue that LOTR lacks a moral compass, these lines should be studied carefully. Tolkien knew how the First Age would influence the Third....and Fourth.

The Silmarillion

The tale of Tuor and Gondolin anticipates the denouement of The Silmarillion as Ulmo cautioned Turgon, "Love not too well the work of thy hands and the devices of thy heart; and remember that the true hope of the Noldor lieth in the West and cometh from the Sea." We recall how integral was the sea to Tolkien's creation myth. Further, Tuor's (Adan) marriage to Idril (Elf) produces Earendil whose voyage changed history. In the tale, lust takes many forms, causing for example Maeglin's desire for Idril, whose prudence and foresight led to the construction of her secret escape tunnel. All too familiar are the results: Maeglin betrays Gondolin's location to Morgoth. Tuor kills Maeglin, and Glorifindel plummets into the abyss fighting the Balrog.

The Lord of the Rings

The Tuor chapter offers an interesting moral assessment that might be used to evaluate LOTR. Tolkien apparently believes that once evil is set in motion, interdiction on earth remains problematic. His conservative Catholicism seemed to vacillate between God as merciful; yet quite just. Melkor's lust for the Silmaril seems mitigated by his desire to see all elves destroyed, so he bides his time. Recalling the creation myth, immortality becomes a curse. What then is God's role? The chapter concludes with silence. What if one knocks on the door of Heaven and no one answers: "Manwe moved not; and of the councils of his heart what tale shall tell?" In LOTR, many times, the company seems to despair: the 'loss' of Gandalf, the defection of Boromir, Frodo and Sam on Mt. Doom. Certainly there is little hope; even Galadriel warns that the quest stands on the edge of a knife, but Tolkien does believe that evil will mar evil. If Gandalf had not been 'lost,' he might not have been able to counter Saruman: "I am Gandalf the White, who has returned from death...[and] Strange are the turns of fortune! Often does hatred hurt itself." As a consequence, the Palantir is discovered, without which the ring might not have been destroyed. (The Voice of Saruman). Illuvatar blends the discord of Melkor with his own, and a more beautiful theme emerges. In Catholic terms, the fall becomes fortunate allowing the redemption.

The Silmarillion

Earendil (the Mariner, the Blessed) posits hope, which for Tolkien must not have always been easy. Losing his parents by age 12, most of his friends in WWI, and clerical opposition to his marriage must collectively have seemed almost too much to endure. His Catholicism was both a source of hope and torment: the former, obviously for heaven, but the latter because of an over - scrupulous conscience. Ironically for those without a spiritual vision, from evil comes good. The evil seems unbounded: 1-Feanor's oath and the kinslaying, 2-the maiming of Beren, and the killing of his son Dior, 3-the murder of Thingol and the ruin of Doraith. Yet, Tolkien, recalling the fortunate fall, sees the Silmarils as "...a healing and a blessing..." for their beauty and curse prompt Earendil's great voyage to the Blessed Realm in defiance of the ban. Ulmo declares: "Shall mortal Man step living upon the undying lands, and yet live?" In the fullness of time, however, the Valar, in the Battle of the Powers, defeat Melkor, but evil lingers. As a reward, perhaps reminiscent of the ending of Job, wherein God rewards Job for his tenacity, but punishes his comforters, Earendil and the Silmaril remain in the heavens as a beacon of hope. Tolkien's alludes to Cynewulf's Christ: "Hail Day Star! Brightest angel sent to man throughout the earth, and Thou steadfast splendour of the sun, bright above stars! Ever Thou dust illumine with Thy light the time of every season...Thou come and shed Thy light on those who long ere this, compassed about with mist and in the darkness...Now we are full of hope..." (Kennedy Translation). Perhaps Tolkien also had in mind another Anglo-Saxon poem, The Seafarer, which chronicles the mariner's search for God. Melkor's chaining recalls his earlier defeats, but evil does linger, for the hate "...sowed in the hearts of Elves and Men are a seed that does not die and cannot be destroyed; and ever and anon it sprouts anew, and will bear dark fruit even until the latest days." Feanor's' remaining sons bear witness. Maedhros, in "anguish and despair" casts himself and the silmaril into a fiery pit, and Maglor, "singing in pain and regret" cast his into the sea. Ironically, we recall the creation music and the themes of Illuvatar and Melkor. Thus ends The Silmarillion.

The Lord of the Rings

Earendil's tale and his descendents define the morality of LOTR. His son is Elrond, and Aragorn can trace his lineage through Elendil and Isildur to Earendil; both, at the risk of over- or misusing the appellation, "Christ figures." Aragorn's succession is validated in The Steward and The King, but its special poignancy cannot be truly appreciated without the backstory. From what seems baron and cold, Gandalf reminds Aragorn of a sapling descended from " ...the Eldest of Trees," Telperion. Aragorn accepts the crown, repeating Elendil's words, "Out of the Great Sea to Middle-earth I am come. In this place will I abide, and my heirs, unto the ending of the world." These events are chronicled in Akallabeth, The Downfall of Numenor.

Akallabeth, The Downfall of Numenor

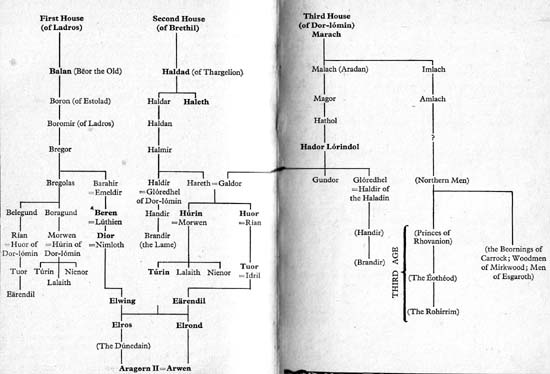

The Edain, the second ones, are men and consist of three houses:

By the will of Illuvatar, they dwelt in the isle of Numenor (see map above), and elves call them the Dunedain As the table notes, several married Elves, as Tolkien dramatizes mortality and immortality exist in all of us. Elrond, for example, chose the first born, while his brother Elros did not. Tolkien's God imposes limits. Although in sight of the Blessed Realm, a travel ban was proclaimed, lest man seek what Illuvatar did not grant them: immortality. Nonetheless, as referenced above, the Firstborn, desiring friendship, brought the Numenorians many gifts including the White Tree, a descendent of Telperion., but Melkor lurks...

The Numenorians lusted for immortality and rejected the cornerstone of faith: acceptance of what appears to be absurd: "For of us is required a blind trust, and a hope without assurances, knowing not what lies before us in a little while." Desire assaults patience: we all want what we cannot or should not have. Truth lies under Melkor's shadow. Clearly for Tolkien, unbridled desire is a sin.

Sauron's time has come; men are ripe for the rings of power. Tolkien constructs character archetypes of good and evil. The evil lust; the good renounce as Yoda cautioned Luke. The last Numenorian king, Arz-Pharazon, determined to humble Sauron and use his might. The familiar warnings appear:

Reminiscent of Genesis' golden calf, or Dracula, Sauron / Melkor is worshiped and death follows; yet Elendil refrained. Pharazon leads a fleet to invade the Blessed Realm; at the last minute he almost relents, but : "...pride was now his master." A cataclysm follows reminiscent of Atlantis, "Numenor went down into the sea," Pharazon is lost, and worst of all, the Edain are sundered from Aman forever. Ships bearing Elendil, and his sons Isildur and Anarion, however, are spared, and they sail to Middle-earth to found kingdoms there. Sauron retreats to Barad-dur, with his great ring. Tolkien notes (like a vampire) he can assume many forms.

Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age

Hrothgar's 'anti-pride' speech,

This verse I have said for thee,

wise from lapsed winters. Wondrous seems

how to sons of men Almighty God

in the strength of His spirit sendeth wisdom,

estate, high station: He swayeth all things.

Whiles He letteth right lustily fare

the heart of the hero of high-born race, --

in seat ancestral assigns him bliss,

his folk's sure fortress in fee to hold,

puts in his power great parts of the earth,

empire so ample, that end of it

this wanter-of-wisdom weeneth none.

So he waxes in wealth, nowise can harm him

illness or age; no evil cares

shadow his spirit; no sword-hate threatens

from ever an enemy: all the world

wends at his will, no worse he knoweth,

till all within him obstinate pride

waxes and wakes while the warden slumbers,

the spirit's sentry; sleep is too fast

which masters his might, and the murderer nears,

stealthily shooting the shafts from his bow!

Under harness his heart then is hit indeed

by sharpest shafts; and no shelter avails

from foul behest of the hellish fiend.1

Him seems too little what long he possessed.

Greedy and grim, no golden rings

he gives for his pride; the promised future

forgets he and spurns, with all God has sent him,

Wonder-Wielder, of wealth and fame.

Yet in the end it ever comes

that the frame of the body fragile yields,

fated falls; and there follows another

who joyously the jewels divides,

the royal riches, nor recks of his forebear.

Ban, then, such baleful thoughts, Beowulf dearest,

best of men, and the better part choose,

profit eternal; and temper thy pride,

warrior famous! The flower of thy might

lasts now a while: but erelong it shall be

that sickness or sword thy strength shall minish,

or fang of fire, or flooding billow,

or bite of blade, or brandished spear,

or odious age; or the eyes' clear beam

wax dull and darken: Death even thee

in haste shall o'erwhelm, thou hero of war!

defines much of this final chapter; Sauron repented but in fear, but "...he was unwilling to return in humiliation and to receive from the Valar a sentence, it might be, of long servitude in proof of his good faith." Most importantly, the Elves in Eriador forge the Rings of Power, secretly guided by Sauron who of course himself forged the one that could control the rest:

--Narya (ring of fire)-given to Gandalf by Cirdan

--Nenya (ring of water, ring of Adamant)-worn by Galadriel

--Vilya (ring of sapphire)--given by Gil-galad to Elrond

These were much sought after by Sauron since they "could ward off the decays of time and postpone the weariness of the world," but recall how the Elves view their own immortality. The evil of the rings consists in providing their wearers a "...desired secret power beyond the measure of their kind." Tolkien's Medieval perspective probably defines the ontology: the great chain of being (Lovejoy, Tillyard). To desire more than what God allows, even if the place seems unfair or even cruel, negates His plan. We know from LOTR that once divided, the company sees only a part of the whole, and each, therefore, in his/her own way contributes to Frodo's quest. Throughout this text, Tolkien has implied that Men and Dwarves delved too deeply...lusted for the material. Sauron may be evil, but like Hitler, could very well assess and exploit weaknesses. Thus seven rings for the Dwarves and nine for Men, the latter especially being most prone to misuse them. Hence the Nazgul are "...under the domination of the One which was Sauron's." Tolkien's description of Sauron's lust for power and ability to control, despite his dislike of allegory, strong parallel Hitler's megalomania. Perhaps rather than allegory, he identifies an archetype.

Geographically, Tolkien describes how Elendil and his sons, Isildur and Anarion found in Middle Earth, Gondor (the Southern Kingdom), and Arnor (the Northern Kingdom) of men: In Gondor is the city of Osgiliath, Minas Ithil (Tower of the Rising Moon / house of Isildur), Minas Anor (Tower of the Setting Sun / house of Anarion).

In Numenor was kept the Seven Stones of much importance in the Trilogy, and the White Tree (from Nimloth, tracing its ancestry to Telperion., which Yavanna grew, from which were made the stars of Varda). The Stones, gave the Numenorians power to "...perceive in them things far off..." The Palantir of course figures predominately in Sauron's fall, through ironically the curiosity of a Hobbit.

Of critical importance to LOTR is Sauron's assault, capturing Minas Ithil (renamed Minas Morgul), and the Last Alliance of Elves and men against him at Dagorlad. This battle is briefly shown in Jackson's movie. The Alliance (led by Elendil, wielding Narsil and Gil-galad) seem to have the day. Tolkien's narrative, here sets the perspective for the Third Age: "But at last the siege was so straight that Sauron himself came forth; and he wrestled with Gil-galad and Elendil, and they both were slain, and the sword of Elendil broke under him as he fell. But Sauron also was thrown down, and with the hilt-shard of Narsil, Isildur cut the Ruling Ring from the hand of Sauron and took it for his own. Then Sauron was for that time vanquished..."

...AND THE THIRD AGE BEGINS...with again an Anglo-Saxon reference. Isildur as we know keeps the ring, as wergild for his father's death. From a Christian perspective, revenge begets revenge as in Beowulf, so the ring "avenged its maker," Isildur is killed by orcs, and the ring is lost in the Great River until.... Subsequently, Elrond predicts that Narsil will not be reforged until Isildur's heir appears to challenge Sauron.

Tolkien believes that of the races: Wizards, Elves, Men, Dwarves and Hobbits, men are the most susceptible to corruption. Numenorians quarrel, and their might wains, but Gondor seems to endure; Minas Anor becomes Minas Tirith, but Minas Ithil becomes Minas Morgul. Important of course for LOTR, when the line of Numenorian kings fail, the Stewards rule until someone returns...

Wizards too are not immune to pride's lustful strides; Saruman resented those who thought Gandalf should lead the High Council. "...Saruman begrudged them that, for his pride and desire of mastery was grown great...Saruman now began to study the lore of the Rings of Power...."

And as the tale ends, we read that "Frodo the Halfling, it is said at the bidding of Mithrandir took on himself the burden, and alone with his servant he passed through peril and darkness and cam at last in Sauron's despite even to Mt. Doom; and threw it into the Fire where it was wrought he cast the Great Ring of Power, and so at least it was unmade and its evil consumed."

Conclusion and Reflection

One could spend a lifetime immersed in The Silmarillion with little time for other pursuits; yet Christopher Tolkien's editions of his father's papers demonstrate that text is but a glimpse into a much vaster world. Nonetheless, a consideration of The Silmarillion should precede LOTR. Clearly, Tolkien intended at least the following parallels: