CHAPTER XIV---TWO CULTURES

I. KNOX KNEW SOPHIE WOULD FIND THE CARDS: (REMEMBER THE PHILOSOPHICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE POINT OF VIEW GAARDER IS USING.) IN THAT CONNECTION LOOK AT PAGE 147 CAREFULLY. WHAT DOES KNOX BELIEVE ABOUT THE ANALOGY BETWEEN CHRISTIANITY AND HILDE? THIS TOO IS AN IMPORTANT FORESHADOWING MOMENT.

II. INDO-EUROPEANS:

A. ORIGIN OF GREEK PHILOSOPHY AND THE CONTEST BETWEEN GOOD AND EVIL.

B. THE VIEW OF HISTORY AS CYCLE:--REMEMBER THAT EPIC POETRY USES A TECHNIQUE OF ORAL COMPOSITION CALLED 'RING STRUCTURE'.

1. THE RING STRUCTURE OF HOMER, PLATO, THE BEOWULF POET

2. WHAT ARE THE MORAL IMPLICATIONS?

C. THE RELIABILITY OF SIGHT AND INSIGHT; what does the term mean philosophically?

III. THE SEMITES AND MONOTHEISM:

A. JUDAISM, CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM-why is land so important in the Middle East? It would be instructive to discover what Rousseau argued about the source of evil as he redefined the Genesis myth..

B. WHAT IS THE GREEK INFLUENCE?

C. LINEAR VIEW OF HISTORY--what does this CHRISTIAN VIEW PRESUPPOSE?

D. THE RELIANCE ON HEARING (“HEAR OH ISRAEL”.)

E. THE IDEA HERE IS NOT CYCLE, BUT TO BE CALLED TO GOD.

F. JESUS AND HIS DISCIPLES... PAUL.

1. GREEK PHILOSOPHY VS. CHRISTIAN REDEMPTION.

2. IS THE GOOD OF PLATO THE GOD OF CHRISTIANITY?

G. THE NOTION OF GOD IS PERSONAL--THIS IDEA WILL BE VERY IMPORTANT IN THE ENLIGHTENMENT WHICH LOOKED TO CLASSICAL PHILOSOPHY FOR WISDOM. CAN A PERSONAL GOD CO-EXIST WITH THE GOD OF REASON, OR DEISM. CLICK HERE FOR DETAILS.

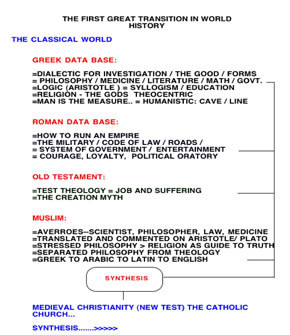

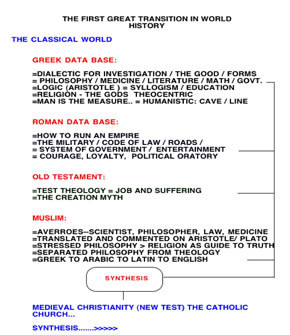

IV. THE PROGRESSION:

A.THE GODS OF HOMER WERE REPLACED BY? WHAT WAS THE LONG AND SHORT TERM EFFECT? FANS OF STAR TREK (ToS) MIGHT RECALL WHAT CAPT. KIRK HAD TO SAY...

B. THE GOD OF CHRISTIANITY. WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE CHRISTIAN VIEW AND THE HOMERIC PERSPECTIVE? COULD HOMER FORESEE THE CHANGE?

V. SOPHIE’S REACTION--MAN AND APE??? WHAT IS THE GREAT SYNTHESIS IN HUMAN HISTORY THAT IS ABOUT TO OCCUR?

TO ANTICIPATE HEGEL DIALECTICALLY

THESIS:

ANTITHESIS:

SYNTHESIS:

SUPPLEMENTARY READING

[Recall that Project Perseus has the classical canon with sophisticated search engines.]

Read BELOW the following selections from:

Look at the excerpts comparatively, and what do you conclude?...

The Iliad

By Homer

Book I

Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another.

And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant's wreath and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs.

"Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove."

On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. "Old man," said he, "let me not find you tarrying about our ships, nor yet coming hereafter. Your sceptre of the god and your wreath shall profit you nothing. I will not free her. She shall grow old in my house at Argos far from her own home, busying herself with her loom and visiting my couch; so go, and do not provoke me or it shall be the worse for you."

The old man feared him and obeyed. Not a word he spoke, but went by the shore of the sounding sea and prayed apart to King Apollo whom lovely Leto had borne. "Hear me," he cried, "O god of the silver bow, that protectest Chryse and holy Cilla and rulest Tenedos with thy might, hear me oh thou of Sminthe. If I have ever decked your temple with garlands, or burned your thigh-bones in fat of bulls or goats, grant my prayer, and let your arrows avenge these my tears upon the Danaans."

Thus did he pray, and Apollo heard his prayer. He came down furious from the summits of Olympus, with his bow and his quiver upon his shoulder, and the arrows rattled on his back with the rage that trembled within him. He sat himself down away from the ships with a face as dark as night, and his silver bow rang death as he shot his arrow in the midst of them. First he smote their mules and their hounds, but presently he aimed his shafts at the people themselves, and all day long the pyres of the dead were burning.

For nine whole days he shot his arrows among the people, but upon the tenth day Achilles called them in assembly- moved thereto by Juno, who saw the Achaeans in their death-throes and had compassion upon them. Then, when they were got together, he rose and spoke among them.

"Son of Atreus," said he, "I deem that we should now turn roving home if we would escape destruction, for we are being cut down by war and pestilence at once. Let us ask some priest or prophet, or some reader of dreams (for dreams, too, are of Jove) who can tell us why Phoebus Apollo is so angry, and say whether it is for some vow that we have broken, or hecatomb that we have not offered, and whether he will accept the savour of lambs and goats without blemish, so as to take away the plague from us."

The Odyssey

Book I

Now Neptune had gone off to the Ethiopians, who are at the world's

end, and lie in two halves, the one looking West and the other East.

He had gone there to accept a hecatomb of sheep and oxen, and was

enjoying himself at his festival; but the other gods met in the house

of Olympian Zeus, and the sire of gods and men spoke first. At that

moment he was thinking of Aegisthus, who had been killed by

Agamemnon's son Orestes; so he said to the other gods:

"See now, how men lay blame upon us gods for what is after all nothing

but their own folly. Look at Aegisthus; he must needs make love to

Agamemnon's wife unrighteously and then kill Agamemnon, though he

knew it would be the death of him; for I sent Mercury to warn him

not to do either of these things, inasmuch as Orestes would be sure

to take his revenge when he grew up and wanted to return home. Mercury

told him this in all good will but he would not listen, and now he

has paid for everything in full."

Book II

Then Telemachus went all alone by the sea side, washed his hands in

the grey waves, and prayed to Athena

"Hear me," he cried, "you god who visited me yesterday, and bade me

sail the seas in search of my father who has so long been missing.

I would obey you, but the Achaeans, and more particularly the wicked

suitors, are hindering me that I cannot do so."

As he thus prayed, Athena came close up to him in the likeness and

with the voice of Mentor. "Telemachus," said she, "if you are made

of the same stuff as your father you will be neither fool nor coward

henceforward, for Ulysses never broke his word nor left his work half

done. If, then, you take after him, your voyage will not be fruitless,

but unless you have the blood of Ulysses and of Penelope in your veins

I see no likelihood of your succeeding. Sons are seldom as good men

as their fathers; they are generally worse, not better; still, as

you are not going to be either fool or coward henceforward, and are

not entirely without some share of your father's wise discernment,

I look with hope upon your undertaking. But mind you never make common

cause with any of those foolish suitors, for they have neither sense

nor virtue, and give no thought to death and to the doom that will

shortly fall on one and all of them, so that they shall perish on

the same day. As for your voyage, it shall not be long delayed; your

father was such an old friend of mine that I will find you a ship,

and will come with you myself. Now, however, return home, and go about

among the suitors; begin getting provisions ready for your voyage;

see everything well stowed, the wine in jars, and the barley meal,

which is the staff of life, in leathern bags, while I go round the

town and beat up volunteers at once. There are many ships in Ithaca

both old and new; I will run my eye over them for you and will choose

the best; we will get her ready and will put out to sea without delay."

Hesiod

from the Theogony

Click here to access The Theogony: read the opening of book one on the creation of the universe and man.

The Golden Age of Greece and Sophocles

Please click here to access the site.

Plato

from the Timaeus

Tim. All men, Socrates, who have any degree of right feeling, at the beginning of every

enterprise, whether small or great, always call upon God. And we, too, who are going to

discourse of the nature of the universe, how created or how existing without creation, if we be not

altogether out of our wits, must invoke the aid of Gods and Goddesses and pray that our words

may be acceptable to them and consistent with themselves. Let this, then, be our invocation of the

Gods, to which I add an exhortation of myself to speak in such manner as will be most

intelligible to you, and will most accord with my own intent.

First then, in my judgment, we must make a distinction and ask, What is that which always is and

has no becoming; and what is that which is always becoming and never is? That which is

apprehended by intelligence and reason is always in the same state; but that which is conceived

by opinion with the help of sensation and without reason, is always in a process of becoming

and perishing and never really is. Now everything that becomes or is created must of necessity

be created by some cause, for without a cause nothing can be created. The work of the creator,

whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an

unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect; but when he looks to the

created only, and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect. Was the heaven then or the world,

whether called by this or by any other more appropriate name-assuming the name, I am asking a

question which has to be asked at the beginning of an enquiry about anything-was the world, I

say, always in existence and without beginning? or created, and had it a beginning? Created, I

reply, being visible and tangible and having a body, and therefore sensible; and all sensible

things are apprehended by opinion and sense and are in a process of creation and created. Now

that which is created must, as we affirm, of necessity be created by a cause. But the father and

maker of all this universe is past finding out; and even if we found him, to tell of him to all men

would be impossible. And there is still a question to be asked about him: Which of the patterns

had the artificer in view when he made the world-the pattern of the unchangeable, or of that

which is created? If the world be indeed fair and the artificer good, it is manifest that he must

have looked to that which is eternal; but if what cannot be said without blasphemy is true, then to

the created pattern. Every one will see that he must have looked to, the eternal; for the world is

the fairest of creations and he is the best of causes. And having been created in this way, the

world has been framed in the likeness of that which is apprehended by reason and mind and is

unchangeable, and must therefore of necessity, if this is admitted, be a copy of something. Now

it is all-important that the beginning of everything should be according to nature. And in

speaking of the copy and the original we may assume that words are akin to the matter which

they describe; when they relate to the lasting and permanent and intelligible, they ought to be

lasting and unalterable, and, as far as their nature allows, irrefutable and immovable-nothing less.

But when they express only the copy or likeness and not the eternal things themselves, they need

only be likely and analogous to the real words. As being is to becoming, so is truth to belief. If

then, Socrates, amid the many opinions about the gods and the generation of the universe, we are

not able to give notions which are altogether and in every respect exact and consistent with one

another, do not be surprised. Enough, if we adduce probabilities as likely as any others; for we

must remember that I who am the speaker, and you who are the judges, are only mortal men, and

we ought to accept the tale which is probable and enquire no further.

Soc. Excellent, Timaeus; and we will do precisely as you bid us. The prelude is charming, and is

already accepted by us-may we beg of you to proceed to the strain?

Tim. Let me tell you then why the creator made this world of generation. He was good, and the

good can never have any jealousy of anything. And being free from jealousy, he desired that all

things should be as like himself as they could be. This is in the truest sense the origin of creation

and of the world, as we shall do well in believing on the testimony of wise men: God desired that

all things should be good and nothing bad, so far as this was attainable. Wherefore also finding

the whole visible sphere not at rest, but moving in an irregular and disorderly fashion, out of

disorder he brought order, considering that this was in every way better than the other. Now the

deeds of the best could never be or have been other than the fairest; and the creator, reflecting on

the things which are by nature visible, found that no unintelligent creature taken as a whole was

fairer than the intelligent taken as a whole; and that intelligence could not be present in anything

which was devoid of soul. For which reason, when he was framing the universe, he put

intelligence in soul, and soul in body, that he might be the creator of a work which was by nature

fairest and best. Wherefore, using the language of probability, we may say that the world became

a living creature truly endowed with soul and intelligence by the providence of God.

This being supposed, let us proceed to the next stage: In the likeness of what animal did the

Creator make the world? It would be an unworthy thing to liken it to any nature which exists as a

part only; for nothing can be beautiful which is like any imperfect thing; but let us suppose the

world to be the very image of that whole of which all other animals both individually and in their

tribes are portions. For the original of the universe contains in itself all intelligible beings, just as

this world comprehends us and all other visible creatures...

Now God did not make the soul after the body, although we are speaking of them in this order;

for having brought them together he would never have allowed that the elder should be ruled by

the younger; but this is a random manner of speaking which we have, because somehow we

ourselves too are very much under the dominion of chance. Whereas he made the soul in origin

and excellence prior to and older than the body, to be the ruler and mistress, of whom the body

was to be the subject.

Now when the Creator had framed the soul according to his will, he formed within her the

corporeal universe, and brought the two together, and united them centre to centre. The soul,

interfused everywhere from the centre to the circumference of heaven, of which also she is the

external envelopment, herself turning in herself, began a divine beginning of never ceasing and

rational life enduring throughout all time. The body of heaven is visible, but the soul is invisible,

and partakes of reason and harmony, and being made by the best of intellectual and everlasting

natures, is the best of things created...And when reason, which works with equal truth, whether she

be in the circle of the diverse or of the same-in voiceless silence holding her onward course in the

sphere of the self-moved-when reason, I say, is hovering around the sensible world and when the

circle of the diverse also moving truly imparts the intimations of sense to the whole soul, then arise

opinions and beliefs sure and certain. But when reason is concerned with the rational, and the circle

of the same moving smoothly declares it, then intelligence and knowledge are necessarily perfected...

When the father creator saw the creature which he had made moving and living, the created

image of the eternal gods, he rejoiced, and in his joy determined to make the copy still more like

the original; and as this was eternal, he sought to make the universe eternal, so far as might be.

Now the nature of the ideal being was everlasting, but to bestow this attribute in its fullness upon

a creature was impossible. Wherefore he resolved to have a moving image of eternity, and when

he set in order the heaven, he made this image eternal but moving according to number, while

eternity itself rests in unity; and this image we call time. For there were no days and nights and

months and years before the heaven was created, but when he constructed the heaven he created

them also. They are all parts of time, and the past and future are created species of time, which

we unconsciously but wrongly transfer to the eternal essence; for we say that he "was," he "is,"

he "will be," but the truth is that "is" alone is properly attributed to him, and that "was" and "will

be" only to be spoken of becoming in time, for they are motions, but that which is immovably the

same cannot become older or younger by time, nor ever did or has become, or hereafter will be,

older or younger, nor is subject at all to any of those states which affect moving and sensible

things and of which generation is the cause. These are the forms of time, which imitates eternity

and revolves according to a law of number. Moreover, when we say that what has become is

become and what becomes is becoming, and that what will become is about to become and that

the non-existent is non-existent-all these are inaccurate modes of expression. But perhaps this

whole subject will be more suitably discussed on some other occasion.

Time, then, and the heaven came into being at the same instant in order that, having been created

together, if ever there was to be a dissolution of them, they might be dissolved together. It was

framed after the pattern of the eternal nature, that it might resemble this as far as was possible;

for the pattern exists from eternity, and the created heaven has been, and is, and will be, in all

time. Such was the mind and thought of God in the creation of time. The sun and moon and five

other stars, which are called the planets, were created by him in order to distinguish and preserve

the numbers of time; and when he had made-their several bodies, he placed them in the orbits in

which the circle of the other was revolving-in seven orbits seven stars. First, there was the moon

in the orbit nearest the earth, and next the sun, in the second orbit above the earth; then came the

morning star and the star sacred to Hermes, moving in orbits which have an equal swiftness with

the sun, but in an opposite direction; and this is the reason why the sun and Hermes and Lucifer

overtake and are overtaken by each other. To enumerate the places which he assigned to the other

stars, and to give all the reasons why he assigned them, although a secondary matter, would give

more trouble than the primary. These things at some future time, when we are at leisure, may

have the consideration which they deserve, but not at present.

...Thus far in what we have been saying, with small exception, the works of intelligence have been

set forth; and now we must place by the side of them in our discourse the things which come

into being through necessity-for the creation is mixed, being made up of necessity and mind.

Mind, the ruling power, persuaded necessity to bring the greater part of created things to

perfection, and thus and after this manner in the beginning, when the influence of reason got the

better of necessity, the universe was created.

Aristotle

from The Metaphysics, Politics and Nicomachean Ethics

METAPHYSICS

[Recall Aristotle on Causality: formal, efficient, material and final cause.]

That the final cause may apply to immovable things is shown by the distinction of its meanings. For the final cause is not only "the good for something," but also "the good which is the end of some action." In the latter sense it applies to immovable things, although in the former it does not; and it causes motion as being an object of love, whereas all other things cause motion because they are themselves in motion. Now if a thing is moved, it can be otherwise than it is. Therefore if the actuality of "the heaven" is primary locomotion, then in so far as "the heaven" is moved, in this respect at least it is possible for it to be otherwise; i.e. in respect of place, even if not of substantiality. But since there is something--X--which moves while being itself unmoved, existing actually, X cannot be otherwise in any respect. For the primary kind of change is locomotion and of locomotion circular locomotion; and this is the motion which X induces. Thus X is necessarily existent; and qua necessary it is good, and is in this sense a first principle. For the necessary has all these meanings: that which is by constraint because it is contrary to impulse; and that without which excellence is impossible; and that which cannot be otherwise, but is absolutely necessary. Such, then, is the first principle upon which depend the sensible universe and the world of nature. And its life is like the best which we temporarily enjoy. It must be in that state always (which for us is impossible), since its actuality is also pleasure. (And for this reason waking, sensation and thinking are most pleasant, and hopes and memories are pleasant because of them.) Now thinking in itself is concerned with that which is in itself best, and thinking in the highest sense with that which is in the highest sense best. And thought thinks itself through participation in the object of thought; for it becomes an object of thought by the act of apprehension and thinking, so that thought and the object of thought are the same, because that which is receptive of the object of thought, i.e. essence, is thought. And it actually functions when it possesses this object. Hence it is actuality rather than potentiality that is held to be the divine possession of rational thought, and its active contemplation is that which is most pleasant and best. If, then, the happiness which God always enjoys is as great as that which we enjoy sometimes, it is marvellous; and if it is greater, this is still more marvellous. Nevertheless it is so. Moreover, life belongs to God. For the actuality of thought is life, and God is that actuality; and the essential actuality of God is life most good and eternal. We hold, then, that God is a living being, eternal, most good; and therefore life and a continuous eternal existence belong to God; for that is what God is...perfect beauty and goodness do

NICOMACHEAN ETHICS

...that pleasure, though a good, is not praised, is an indication that it is superior to the things we praise, as God and the Good are, because they are the standards to which everything else is referred. For praise belongs to goodness, since it is this that makes men capable of accomplishing noble deeds, while encomia are for deeds accomplished, whether bodily feats or achievements of the mind.

. But for a living being, if we eliminate action, and a fortiori creative action, what remains save contemplation? It follows that the activity of God, which is transcendent in blessedness, is the activity of contemplation; and therefore among human activities that which is most akin to the divine activity of contemplation will be the greatest source of happiness. A further confirmation is that the lower animals cannot partake of happiness, because they are completely devoid of the contemplative activity. The whole of the life of the gods is blessed, and that of man is so in so far as it contains some likeness to the divine activity; but none of the other animals possess happiness, because they are entirely incapable of contemplation. Happiness therefore is co-extensive in its range with contemplation: the more a class of beings possesses the faculty of contemplation, the more it enjoys happiness, not as an accidental concomitant of contemplation but as inherent in it, since contemplation is valuable in itself. It follows that happiness is some form of contemplation. But the philosopher being a man will also need external well--being, since man's nature is not self--sufficient for the activity of contemplation, but he must also have bodily health and a supply of food and other requirements.

POLITICS

Let us then take it as agreed between us that to each man there falls just so large a measure of happiness as he achieves of virtue and wisdom and of virtuous and wise action: in evidence of this we have the case of God, who is happy and blessed, but is so on account of no external goods, but on account of himself, and by being of a certain quality in his nature; since it is also for this reason that prosperity is necessarily different from happiness--for the cause of goods external to the soul is the spontaneous and fortune,2 but nobody is just or temperate as a result of or owing to the action of fortune. And connected is a truth requiring the same arguments to prove it, that it is also the best state, and the one that does well,3 that is happy. But to do well is impossible save for those who do good actions, and there is no good action either of a man or of a state without virtue and wisdom; and courage, justice and wisdom belonging to a state have the same meaning and form as have those virtues whose possession bestows the titles of just and wise and temperate on an individual human being.

THE BOOK OF GENESIS

Creation (Chapters I and II), and The Covenant

In the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless wasteland, and darkness covered the abyss, while a mighty

wind swept over the waters.

Then God said, "Let there be light," and there was light.

God saw how good the light was. God then separated the light from the darkness.

God called the light "day," and the darkness he called "night." Thus evening came, and

morning followed--the first day.

Then God said, "Let there be a dome in the middle of the waters, to separate one body of

water from the other." And so it happened:

God made the dome, and it separated the water above the dome from the water below it.

God called the dome "the sky." Evening came, and morning followed--the second day.

Then God said, "Let the water under the sky be gathered into a single basin, so that the

dry land may appear." And so it happened: the water under the sky was gathered into its

basin, and the dry land appeared.

God called the dry land "the earth," and the basin of the water he called "the sea." God

saw how good it was.

Then God said, "Let the earth bring forth vegetation: every kind of plant that bears seed

and every kind of fruit tree on earth that bears fruit with its seed in it." And so it

happened:

the earth brought forth every kind of plant that bears seed and every kind of fruit tree on

earth that bears fruit with its seed in it. God saw how good it was.

Evening came, and morning followed--the third day.

Then God said: "Let there be lights in the dome of the sky, to separate day from night.

Let them mark the fixed times, the days and the years,

and serve as luminaries in the dome of the sky, to shed light upon the earth." And so it

happened:

God made the two great lights, the greater one to govern the day, and the lesser one to

govern the night; and he made the stars.

God set them in the dome of the sky, to shed light upon the earth,

to govern the day and the night, and to separate the light from the darkness. God saw

how good it was.

Evening came, and morning followed--the fourth day.

Then God said, "Let the water teem with an abundance of living creatures, and on the

earth let birds fly beneath the dome of the sky." And so it happened:

God created the great sea monsters and all kinds of swimming creatures with which the

water teems, and all kinds of winged birds. God saw how good it was,

and God blessed them, saying, "Be fertile, multiply, and fill the water of the seas; and let

the birds multiply on the earth."

Evening came, and morning followed--the fifth day.

Then God said, "Let the earth bring forth all kinds of living creatures: cattle, creeping

things, and wild animals of all kinds." And so it happened:

God made all kinds of wild animals, all kinds of cattle, and all kinds of creeping things

of the earth. God saw how good it was.

Then God said: "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. Let them have

dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and the cattle, and over all the wild

animals and all the creatures that crawl on the ground."

God created man in his image; in the divine image he created him; male and female he

created them.

God blessed them, saying: "Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it. Have

dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and all the living things that move

on the earth."

God also said: "See, I give you every seed-bearing plant all over the earth and every tree

that has seed-bearing fruit on it to be your food;

and to all the animals of the land, all the birds of the air, and all the living creatures that

crawl on the ground, I give all the green plants for food." And so it happened.

God looked at everything he had made, and he found it very good. Evening came, and

morning followed--the sixth day.

(CHAPTER II):

Thus the heavens and the earth and all their array were completed.

Since on the seventh day God was finished with the work he had been doing, he rested

on the seventh day from all the work he had undertaken.

So God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the

work he had done in creation.

Such is the story of the heavens and the earth at their creation. At the time when the

LORD God made the earth and the heavens--

while as yet there was no field shrub on earth and no grass of the field had sprouted, for

the LORD God had sent no rain upon the earth and there was no man to till the soil,

but a stream was welling up out of the earth and was watering all the surface of the

ground--

the LORD God formed man out of the clay of the ground and blew into his nostrils

the breath of life, and so man became a living being.

Then the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and he placed there the

man whom he had formed.

Out of the ground the LORD God made various trees grow that were delightful to look

at and good for food, with the tree of life in the middle of the garden and the tree of the

knowledge of good and bad.

AND...

...Behold I will establish my covenant with you, and with your seed after you:

10 And with every living soul that is with you, as well in all birds as in cattle and beasts of the earth, that are come forth out of the ark, and in all the beasts of the earth.

11 I will establish my covenant with you, and all flesh shall be no more destroyed with the waters of a flood, neither shall there be from henceforth a flood to waste the earth.

12 And God said: This is the sign of the covenant which I will give between me and you, and to every living soul that is with you, for perpetual generations.

13 I will set my bow in the clouds, and it shall be the sign of a covenant between me, and between the earth.

14 And when I shall cover the sky with clouds, my bow shall appear in the clouds:

15 And I will remember my covenant with you, and with every living soul that beareth flesh: and there shall no more be waters of a flood to destroy all flesh.

16 And the bow shall be in the clouds, and I shall see it, and shall remember the everlasting covenant, that was made between God and every living soul of all flesh which is upon the earth.

The New Testament

St. Matthew

AND seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain, and when he was set down, his disciples came unto him.

2 And opening his mouth, he taught them, saying:

3 Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

4 Blessed are the meek: for they shall possess the land.

5 Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

6 Blessed are they that hunger and thirst after justice: for they shall have their fill.

7 Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy.

8 Blessed are the clean of heart: for they shall see God.

9 Blesses are the peacemakers: for they shall be called children of God.

10 Blessed are they that suffer persecution for justice' sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

11 Blessed are ye when they shall revile you, and persecute you, and speak all that is evil against you, untruly, for my sake:

12 Be glad and rejoice, for your reward is very great in heaven. For so they persecuted the prophets that were before you.

13 You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt lose its savour, wherewith shall it be salted? It is good for nothing any more but to be cast out, and to be trodden on by men.

14 You are the light of the world. A city seated on a mountain cannot be hid.

15 Neither do men light a candle and put it under a bushel, but upon a candlestick, that it may shine to all that are in the house.

16 So let your light shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father who is in heaven.

17 Do not think that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets. I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill.

18 For amen I say unto you, till heaven and earth pass, one jot, or one tittle shall not pass of the law, till all be fulfilled.

19 He therefore that shall break one of these least commandments, and shall so teach men, shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven. But he that shall do and teach, he shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

20 For I tell you, that unless your justice abound more than that of the scribes and Pharisees, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.

21 You have heard that it was said to them of old: Thou shalt not kill. And whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment.