Victorian Philosophy

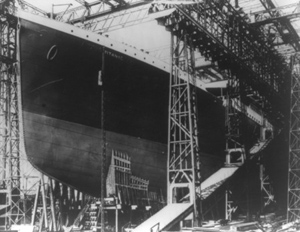

This man helped define the best and worst of the Victorian legacy:

(Edward John Smith)

...he had something to do with this:

...and the date was April 14-15, 1912...

This poem by Thomas Hardy marked the event:

The Convergence Of The Twain

I

In a solitude of the sea

Deep from human vanity,

And the Pride of Life that planned her, stilly couches she.

II

Steel chambers, late the pyres

Of her salamandrine fires,

Cold currents thrid, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres.

III

Over the mirrors meant

To glass the opulent

The sea-worm crawls-grotesque, slimed, dumb, indifferent.

IV

Jewels in joy designed

To ravish the sensuous mind

Lie lightless, all their sparkles bleared and black and blind.

V

Dim moon-eyed fishes near

Gaze at the gilded gear

And query: "What does this vaingloriousness down here?"...

VI

Well: while was fashioning

This creature of cleaving wing,

The Immanent Will that stirs and urges everything

VII

Prepared a sinister mate

For her - so gaily great -

A Shape of Ice, for the time far and dissociate.

VIII

And as the smart ship grew

In stature, grace, and hue,

In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too.

IX

Alien they seemed to be:

No mortal eye could see

The intimate welding of their later history,

X

Or sign that they were bent

by paths coincident

On being anon twin halves of one august event,

XI

Till the Spinner of the Years

Said "Now!" And each one hears,

And consummation comes, and jars two hemispheres.

It has been observed that the Victorian period marked the first time in history that people "knew" they were different? Why, and in what sense did they know? Formulate answers as we read the background material. We have seen that German and English Romanticism influenced the English Romantic period resulting in the epistemological notion that "mind" indeed was over "matter." However, increasing social and economic inequalities as noted by Marx and Engels resulted in great wealth for some [the industrial revolution] but grinding poverty for others. The "pleasure dome" of Coleridge and Shelley's "west wind" seemed irrelevant to the social and economic problems of the industrial revolution. The novel became the most important art form advocating social change, and Dickens' largely autobiographical works dramatized a society that witnessed more technological change in 50 years than in all prior ages. Philosophers quickly saw that this technology had to be managed if for no other reason that at least for some, more leisure time meant the need to make meaningful choices. Hence UTILITARIANISM (meaning utility or useful) became an important philosophical issue involving another great shift from the 17 and 18th century interest in epistemology to ethics in the 19th century. Given the expansion of technology and Darwin's impact on faith, it is logical to observe that people began to wonder what they ought to hold as "good". This is an issue that the philosophy of ethics examines.

For the authors below, you can

Click HERE to access a list of best Victorian web sites.

and,

from the SJC STUDENT CURRICULUM LINKS, a new page has been added for VICTORIAN WEB SITES

Assignments for the Victorian Intellectual Background:

ORGANIZATIONAL OUTLINE:

I. They knew they were different.

A. the industrial revolution--progress and leisure time

B. the march of technology:

C. think of our own century.

D. Technological processes apply our definition of sciences to everyday life, raising moral issues involving time management, and the limits of expansion. What does this picture portray?

Now, read, for example The Cry Of The Children by Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers---

And that cannot stop their tears.

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows;

The young birds are chirping in the nest;

The young fawns are playing with the shadows;

The young flowers are blowing toward the west---

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

They are weeping bitterly!---

They are weeping in the playtime of the others

In the country of the free.

Do you question the young children in the sorrow,

Why their tears are falling so?---

The old man may weep for his to-morrow

Which is lost in Long Ago---

The old tree is leafless in the forest---

The old year is ending in the frost---

The old wound, if stricken, is the sorest---

The old hope is hardest to be lost:

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

Do you ask them why they stand

Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers,

In our happy Fatherland?

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their looks are sad to see,

For the man's grief abhorrent, draws and presses

Down the cheeks of infancy---

"Your old earth," they say, "is very dreary;"

"Our young feet," they say, "are very weak!

Few paces have we taken, yet are weary.

Our grave-rest is very far to seek.

Ask the old why they weep, and not the children,

For the outside earth is cold,---

And we young ones stand without, in our bewildering,

And the graves are for the old.

"True," say the young children, "it may happen

That we die before our time.

Little Alice died last year---the grave is shapen

Like a snowball, in the rime.

We looked into the pit prepared to take her---

Was no room for any work in the close clay:

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her

Crying, 'Get up, little Alice! it is day.'

If you listen by that grave, in sun and shower,

With your ear down, little Alice never cries!---

Could we see her face, be sure we should not know her,

For the smile has time for growing in her eyes---

And merry go her moments, lulled and stilled in

The shroud, by the kirk-chime!

It is good when it happens," say the children,

"That we die before our time."

Alas, alas, the children! they are seeking

Death in life, as best to have!

They are binding up their hearts away from breaking,

With a cerement from the grave.

Go out, children, from the mine and from the city---

Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do---

Pluck your handfuls of the meadow-cowslips pretty---

Laugh aloud, to feel your fingers let them through!

But they answer, "Are your cowslips of the meadows

Like our weeds anear the mine?

Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows,

From your pleasures fair and fine!

"For oh," say the children, "we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap---

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

Our knees tremble sorely in the stooping---

We fall upon our faces, trying to go;

And, underneath our heavy eyelids drooping,

The reddest flower would look as pale as snow.

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring,

Through the coal-dark, underground---

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.

"For, all day, the wheels are droning, turning,---

Their wind comes in our faces,---

Till our hearts turn,---our head, with pulses burning,

And the walls turn in their places---

Turns the sky in the high window blank and reeling---

Turns the long light that droppeth down the wall---

Turn the black flies that crawl along the ceiling---

All are turning, all the day, and we with all.---

And, all day, the iron wheels are droning;

And sometimes we could pray,

'O ye wheels,' (breaking out in a mad moaning)

'Stop! be silent for to-day!' "

Ay! be silent! Let them hear each other breathing

For a moment, mouth to mouth---

Let them touch each other's hands, in a fresh wreathing

Of their tender human youth!

Let them feel that this cold metallic motion

Is not all the life God fashions or reveals---

Let them prove their inward souls against the notion

That they live in you, os under you, O wheels!---

Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward,

Grinding life down from its mark;

And the children's souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark.

Now, tell the poor young children, O my brothers,

To look up to Him and pray---

So the blessed One, who blesseth all the others,

Will bless them another day.

They answer, "Who is God that He should hear us,

White the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us

Pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word!

And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)

Strangers speaking at the door:

Is it likely God, with angels singing round Him,

Hears our weeping any more?

"Two words, indeed, of praying we remember,

And at midnight's hour of harm,---

'Our Father,' looking upward in the chamber,

We say softly for a charm.

We know no other words except 'Our Father,'

And we think that, in some pause of angels' song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong.

'Our Father!' If He heard us, He would surely

(For they call Him good and mild)

Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely,

'Come and rest with me, my child.'

"But no!" say the children, weeping faster,

"He is speechless as a stone;

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on.

Go to!" say the children,---"Up in Heaven,

Dark, wheel-like, turning clouds are all we find.

Do not mock us; grief has made us unbelieving---

We look up for God, but tears have made us blind."

Do you hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye preach?

For God's possible is taught by His world's loving---

And the children doubt of each.

And well may the children weep before you;

They are weary ere they run;

They have never seen the sunshine, nor the glory

Which is brighter than the sun:

They know the grief of man, but not the wisdom;

They sink in man's despair, without its calm---

Are slaves, without the liberty in Christdom,---

Are martyrs, by the pang without the palm,---

Are worn, as if with age, yet unretrievingly

No dear remembrance keep,---

Are orphans of the earthly love and heavenly:

Let them weep! let them weep!

They look up, with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they mind you of their angels in their places,

With eyes meant for Deity;---

"How long," they say, "how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child's heart,

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart?

Our blood splashes upward, O our tyrants,

And your purple shows your path;

But the child's sob curseth deeper in the silence

Than the strong man in his wrath!"

II. Historical retrospective:

A. Medieval--Aristotle, logic, deduction and the Catholic Church

B. Renaissance--Bacon, Galileo, induction, and the rise of the experimental method

C. Seventeenth-Eighteenth Centuries: laws of nature, Newton, progress, heaven on earth

D. Romantic period--the hero "scientist" challenges the gods (Frankenstein)

E. Victorian period--challenge to the microcosm in Sacred Scripture (Darwin) and Social Darwinism: Herbert Spencer.

F. What happened on April 14-15, 1912?

III. The development of the Victorian period:

A. Early Period (1832-1843)

B. Middle Period (1843-1870)

C. Late Period (1870-1901)

IV. A microcosmic overview--read these two poems. If the mimetic theory applies, what do they reveal about Victorian times...

ARNOLD: DOVER BEACH AND BROWNING'S MY LAST DUCHESS.

Dover Beach:

by Matthew Arnold

[Hint: note the classical allusions to Antigone and the metaphor of the sea.]

The sea is calm to - night,

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; - on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon - blanch'd land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand.

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegaean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl'd.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night - wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

My Last Duchess:

by Robert Browning

[Hint: This poem is a dramatic monologue.]

Ferrara

That's my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Fra Pandolf's hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will't please you sit and look at her? I said

"Fra Pandolf" by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, 'twas not

Her husband's presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess' cheek: perhaps

Fra Pandolf chanced to say, "Her mantle laps

Over my lady's wrist too much," or "Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half - flush that dies along her throat:" such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart - how shall I say? - too soon made glad.

Too easily impressed: she liked whate'er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, 'twas all one! My favor at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace - all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men, - good! but thanked

Somehow - I know not how - as if she ranked

My gift of a nine - hundred - years - old name

With anybody's gift. Who'd stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech - (which I have not) - to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, "Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark" - and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

- E'en then would be some stooping; and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene'er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will't please you rise? We'll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master's known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter's self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we'll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea - horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

THE PHILOSOPHICAL / EDUCATIONAL CONTROVERSIES: General introduction to Utilitarianism: BENTHAM and MILL

JEREMY BENTHAM (1784-1832):

Jeremy Bentham said that happiness (material) consists in the greatest good for the greatest number. Note, however, that without the "idealism" of the Romantics, such a (materialistic) altruism would not have been possible. Every object is willed for the pleasure it provides. This is a form of Hedonism. Bentham saw the interest of the community as the sum of the individuals who compose it. People, he believed, are motivated by self-interest, to have pleasure and to avoid pain. In terms of politics, this would seem to suggest democracy, but ironically such views fueled the socialists who argued that if private property causes harm, then it too ought to be abolished. Bentham said:

"The motto or watchword of government ought to be--BE QUIET. For two main reasons: 1. Generally speaking, any interference on the part of government is needless. There is no one who knows what is for your interest, so well as yourself--no one who is disposed with so much ardor and constancy to pursue it. 2. Generally speaking, it is moreover likely to be pernicious by the restraint imposed on free agency of the individual. Pain is the general concomitant of the sense of such restraint, wherever it is experienced...the attachment of the maximum enjoyment will be most effectually secured by leaving each individual to pursue his own maximum of enjoyment...security and freedom are all that industry requires.:

Summary. Bentham believed...

1. All pleasure is physical (spiritual pleasures are only partly satisfactory).

2. Man should only pursue pleasure.

3. The pursuit of pleasure is governed by: intensity / duration / closeness / extent

4. Sanctions or punishments are on several levels:

Links for Bentham:

Click here for primary and secondary source commentary on Bentham from ONLINE GUIDE TO ETHICS AND MORAL PHILOSOPHY.

Background and summary information for Bentham: click here from the Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

Primary source: An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Read Chapters: ONE to FIVE.

JOHN STUART MILL (1806-1873):

Mill disagreed with Bentham that physical pleasure was the highest good. He attempts to fuse the idealism of romanticism with the utilitarianism of Bentham. Mental pleasures, therefore, are superior to physical ones, and since this choice makes pleasure subjective, one ought to consult someone experienced in both. Thus experience and wisdom and judgment are essential, and therefore education is essential--this truth he holds in common with Plato. Pleasure is NOT the standard, so we need to develop one, the most important of which is man's sense of dignity. Mill said:

"No intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no instructed person would be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and consciousness would be selfish and base, even though they should be persuaded that the fool is better satisfied with his loss than they are with theirs. A being of higher faculties requires more to make him happy...it is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be a Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. If the fool is of a different opinion, it is because he only knows his own side of the question."

[NOTE: Mill's Autobiography contains additional comments regarding education and values.] The central question raised was how to maximize individual freedom while keeping order. In the essay on COLERIDGE Coleridge represents the idea of order and philosophical tradition (realism) and Bentham represents progress in the nominalistic sense.]

READING ASSIGNMENTS FOR THE VICTORIAN PERIOD:

1. The following by Mill should be read:

2. The Following from Dickens should be read:

Hard Times: Excerpts from Chapters I, II, and V: Note especially the school room; (Character's names are revealing) as is the description of Coketown. Biblical allusions are significant. What (or who) is being satirized?

Additional full text resources:

(See The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume II. Fifth edition. New York: W.W. Norton, 1986.)

...by Mill:

Utilitarianism (full text provided)

On Liberty (full text provided)

Autobiography (full text: CHAPTER V's references to Wordsworth and Coleridge are important for Mill's mental crisis and recovery.

...by Dickens:

...by Darwin:

Excerpts from ORIGIN OF SPECIES AND DESCENT OF MAN. (On reserve) or click here. Pay particular attention to Darwin's view of God.

THE EDUCATIONAL CONTROVERSY BETWEEN ADVOCATES OF TRADITIONAL LIBERAL ARTS PROPONENTS SUCH AS ARNOLD, AND THOSE ADVOCATING A MORE TECHNICAL EDUCATION SUCH AS HUXLEY CONTINUES TODAY:

HUXLEY, THOMAS: SCIENCE AND CULTURE

ARNOLD, MATTHEW:CULTURE AND ANARCHY AND LITERATURE AND SCIENCE...

EXCERPTS FROM ARNOLD AND HUXLEY: Click here to Return to Table of Contents

AND SEE ALSO: STUDENT CURRICULUM LINKS: VICTORIAN PAGE (NEW)