| Table of Contents |

NEW: DISCUSSION QUESTIONS--BELOW

|

|||||||||||||||

|

HENRY IV, PART ONE, A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS AND RATIONAL FOR A PERFORMANCE: THE PROTOCOL OF HAROLD BLOOM AND A.C. BRADLEY

|

||||||||||||||||

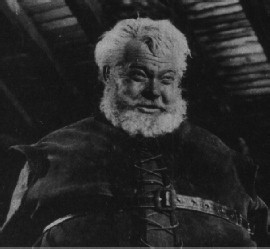

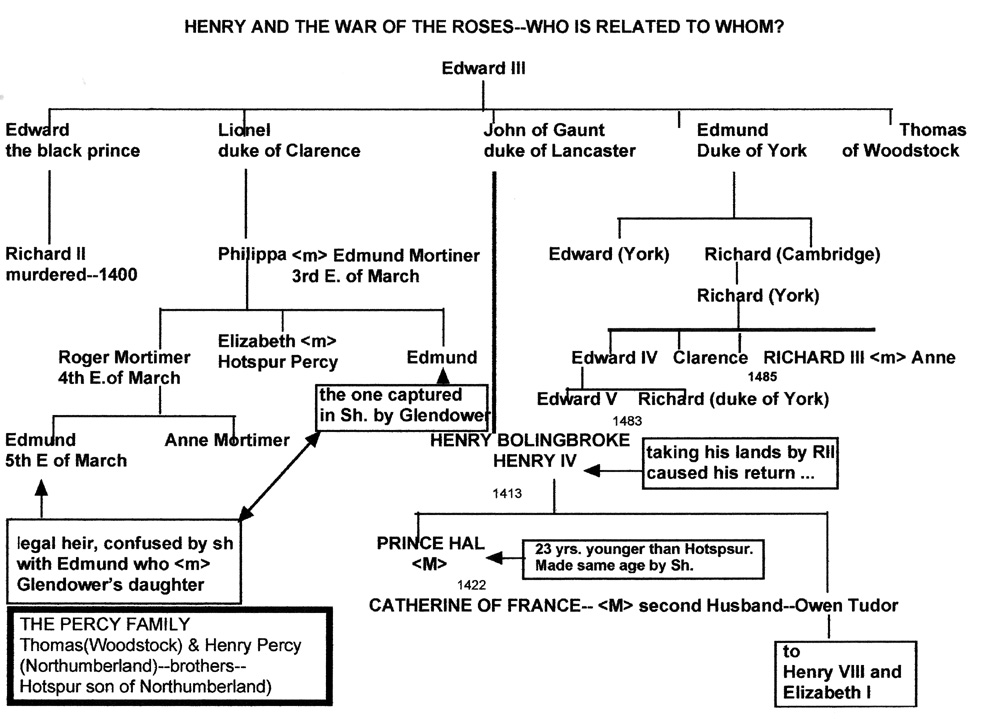

| SHAKESPEARE was interested in making money, so he wrote plays that his audiences wanted to see, and in so doing (as Bloom reminds us in Shakespeare, The Invention of the Human), defined personality--what in means to be human.) Thus, McKellen's Richard III not only dramatizes the rise and fall of a Medieval king, but more significantly probes the darker side of humanity's lust for power: we are taken on a tour of the mind of a dictator: Adolf Hitler, for he too reminds us of a side of our humanity we might rather not face. Bloom after all, tells us in his Macbeth essay that the king so steeped in blood and imagination reminds us most of ourselves. (p. 516 ff).

Thus, McKellen's production subordinated the almost forgotten pragmatics of the War of the Roses to the Nurenberg-like spectacle of Richard qua Hitler, and the play made perfect sense, for Shakespeare in dramatizing the mind of a tyrant touched on a universal. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| What then in I Henry IV will sustain Bloom's thesis, and captivate a modern audience if the rigors of the War of the Roses do not?

We will take our cue from Harold Bloom's study of the play and its characters. Throughout his book, Bloom repeatedly lauds Hamlet and Sir John Falstaff as the characters whom he admires the most, characters whom Shakespeare endows with personalities that transcend time and place--they tell us what it means to be human. Hamlet's intellect embraces all, and Falstaff's wit embraces life. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| What if the focus of our structural analysis is based on Bloom's interpretation of Falstaff? You should read Chapter 17 (pp. 217 ff) of Bloom's book , noting the following:

Wit is Falstaff's god, and since we must assume that God has a sense of humor, we can observe that Falstaff's vitalizing discourse, his beautiful laughing speech...is truly Sir John's mode of devotion...A veteran warrior, now set against the chivalric code of honor, Falstaff knows that history is an ironic flux of reversals. Prince Hal refuses to learn this lesson from Falstaff...One wouldn't want to...carouse with Falstaff, but if you crave vitalism and vitality, then you turn to...Falstaff, the true and perfect image of life itself...Falstaff to most scholars is the emblem of self-indulgence, but to most playgoers and readers, Sir John is the representative of imaginative freedom, or a liberty set against time, death, and the state, which is a condition that we crave for ourselves...Shakespeare essentially invented human personality as we continue to know and value it. Falstaff has priority in this invention [of the human]...the sublime Falstaff simply is not a coward, a court jester or fool, or a confidence man, a bawd, another politician, an opportunistic courtier, an alcoholic seducer of the young. Falstaff is the Elizabethan Socrates, and in the wit combat with Hal, the prince is a mere sophist, bound to lose. Falstaff, like Socrates, is wisdom, wit, self-knowledge, mastery of reality. Socrates too seemed disreputable to the power mongers of Athens.

Instructor's note on the dialectical process: [Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth of Athens by teaching disrespect for the gods, and was executed for treason. Socrates also becomes the great literary persona in Plato's dialogues who in advancing the theory of the forms etc., manages to outrage the sophists, the professional educators of the day, who cannot argue consistently or in depth. He refutes their arguments on the nature of justice, education etc. with ease, and of course those in authority cannot abide refutation.]

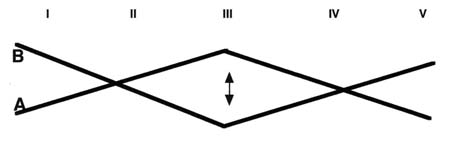

1--the first funeral oration of Pericles (from Thucydides' History)... 2--The Sophists: In the Athenian experiment in democracy, the ability to think and speak well were necessary conditions for survival. According to one critic: "One of the solvents of traditional values was an intellectual revolution...a critical evaluation of accepted ideas in every sphere of thought. It stemmed from innovations in education. Democratic institutions had created demand for an education that would prepare men for public life...the demand was met by the appearance of the professional teacher, the Sophist...who taught, for a fee, not only the techniques of public speaking but also the subjects which gave a man something to talk about-government, ethics etc. The curriculum of the sophists mark the first appearance of European civilization of the liberal education. The sophists were great teachers, but like most teachers they had little control over their teaching. They produced a generation that had been trained to see both sides of any question and to argue the weaker side as effectively as the stronger, the false as effectively as the true, to argue inferentially from probability in the absence of concrete evidence...rather than to accepted moral standards...The emphasis on the technique of effective presentation of both sides of any case encouraged a relativistic point of view, and finally produced a cynical mood which denied the existence of any absolute standards. (from The Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces. Volume 1 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1985, p. 7ff. Written by Bernard Knox.) Socrates objected to the decline of standards, and used the dialectical process to force the sophists to see the limitations of their methods... 3--DEFINITION OF THE DIALECTICAL PROCESS FROM THE REPUBLIC of PLATO: PREMISE: Does Falstaff use the dialectical process to test the assumptions of the other characters...? result? "Embowelled? if thou embowel me today...come you along with me." [V,iv,110-28] He adds the following: Shakespearean secularists should manifest their Bardoaltry by celebrating the Resurrection of Sir John Falstaff. It should be made, unofficially but pervasively, an international holiday, a Carnival of wit, with multiple performances of Henry IV, Part One. Let it be a day of loathing political ambition, religious hypocrisy, and false friendship... If Bloom is correct, we should be able to develop strategies for a successful production using Falstaff as the focus. We will use a model for the tragedies suggested by A.C. Bradley in his Shakespearean Tragedy. The following scheme has been suggested to dramatize the universals (recall Aristotle) in a Shakespeare play--note that it is different from the 'triangle' learned in earlier classes. Let A stand for one major element the play's central conflict, and let B stand for the other. What happens is that B descends to Act III and rises, while A does the converse. Each scene in the play is primarily an A or B scene, and the tension between the two elements propels the conflict of the play as the universals are dramatized.

Project: You are going to develop a scheme for producing a film of this play. We know that a version requiring a degree in English history will not work, so we will construct the A / B model based on Falstaff. Therefore certain editorial decisions will have to be made about plot, character, setting, use of language etc. that will result in what will make a good film. Methodology: EXAMINE THE FOLLOWING STRUCTURE BASED ON BRADLEY'S MODEL (See: Shakespearean Tragedy, a link to which may be found on the site's index page.)

1--Determine what A will stand for:__________________________ 2--Determine what B will stand for:__________________________ NOTE THE FOLLOWING AS PROMPTS: WHAT WOULD AN AMERICAN AUDIENCE WOULD WANT TO SEE GIVEN YOUR ASSESSMENT OF THE CURRENT POLITICAL CLIMATE? [REMEMBER HOW RICHARD III WAS FILMED WITH RICHARD AS HITLER:].

THE QUESTION IS NOW HOW WILL THIS BE PRESENTED--RECALL THE PRAGMATIC THEORY? 3. RECALL THE THEME PASSAGE (IN ACT I), AND THE KEY MOTIFS TO INCLUDE THE SUN AND CLOUDS. 4. AS WITH TAMING OF THE SHREW, APPEARANCE VS. REALITY IS IMPORTANT. Label each scene in the play as A or B or maybe some combination of both: ACT I: scene 1=______________ 2=_______________ 3=______________ ACT II: scene 1=_______________2=________________3=______________4=_____________ ACT III: scene 1=_______________2=________________3=______________ ACT IV: scene 1=______________2=_________________3=______________4=______________ ACT V scene 1=______________2=_________________3=_______________4=_____________ |

||||||||||||||||

|

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR HENRY IV, PART I

[Determine for each scene its A / B protocol.] I.i 1. Examine Worcester's first lines in the scene. What is revealed about him?

V,ii |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||