|

"Building subject area expertise or developing an awareness of the potential value of an isolated piece of information does not occur overnight," she said. "It is developed over time."

|

|||||

TABLE OF CONTENTS: MODERN PERIOD

RETURN TO 'HAMLET AND THE DAEMONS' CHAPTER TWO

Introduction to Classical Philosophy and Medieval Philosophy

The study of formal philosophy at first seems like a foreign language, with the reaction taking the form of: "Do people really talk this way, and why?" The answer is, "Yes, they do," and the reasons are complex. Sooner or later, most people, especially in times of trouble ask, "Why me?" or "It isn't fair" or "Why would God allow this to happen to...." Especially after 9-11 and the continuing threat of terrorism, people have come to understand that simply and pragmatically to trust technology without moral and analytical contexts invites tragedy and threatens survival. Further astute commentators such as FBI Agent Coleen Rowley warned that the lack of critical thinking and analytical skills may well have made September 11 inevitable.

|

"Building subject area expertise or developing an awareness of the potential value of an isolated piece of information does not occur overnight," she said. "It is developed over time."

|

|||||

Testifying before Members of the Senate Judiciary Committee's Oversight Hearings on Counterterrorism on June 6, 2002, she noted:

Philosophy attempts to answer her concerns, and whether we know it or admit it, we at one time or another have asked these questions and are philosophers. T.S. ELIOT NOTED THAT IF WE ARE MORE INTELLIGENT THAN OUR PREDECESSORS, IT IS BECAUSE WE HAVE LEARNED SO MUCH FROM THEM. ELIOT CORRECT, BUT WHAT IF WE HAVE DECIDED THE PAST IS NOT WORTH THE INVESTIGATIVE TIME? WE HAVE CEASED TO MAKE THE CONNECTIONS NECESSARY FOR PROVIDING SOLUTIONS TO OUR MOST ESSENTIAL GOAL: SURVIVAL AS A SPECIES.

ROWLEY is correct, as the issues she addresses are philosophical, making the discipline NOT a synthesis of abstract irrelevancies, but very much a state of mind needed for our survival. This course will study the past for the purpose of illuminating the present and ensuring the future.

|

|

|||

PRELIMINARY MATTERS:

To study philosophy involves learning new vocabulary. After sufficient exposure, you will use it with as much ease as what you know today. The material is abstract, and abstract thinking requires effort and concentration, both in study and in application to the literature.

Philosophy asks ONE QUESTION: "WHAT IS IT REASONABLE TO BELIEVE?"

With most simple questions, the answers are complex. Reasonable to whom? What about faith? Do I have to experience it to believe it? Believe what? What is worth believing etc.?

We have to systematize the material, and traditionally philosophy has involved three branches of study:

Metaphysics: Metaphysical questions are the most fundamental. Essentially, they ask, "What is really real?" " What is the nature of reality?" Of course everything else depends on this, and the answer is not as simple as it may appear. BE PREPARED TO HAVE YOUR COMMON SENSE ASSUMPTIONS CHALLENGED. Plato's dialectical process begins with the notions that intellectual and moral growth depends on the willingness of someone to "treat first principles [deeply held convictions that we never challenge] as assumptions [that must be challenged if growth is to occur.] Words such as "IS" "SUBSTANCE" "ESSENCE" have metaphysical connotations. Metaphysical REALISM suggests that the true nature of reality (the idea) is essentially spiritual. The substantial nature of existence transcends the changing physical world--the Judeo-Christian systems postulate such a view. Metaphysical NOMINALISM argues that the nature of reality is physical. What we observe with our senses is real. Most scientists and philosophers such as Locke accept this view. Some scientists and philosophers are PRAGMATISTS, stating as the sophists in ancient Greece that reality cannot be known with absolute certitude. The individual builds an experiential base by solving problems. The American educational philosopher John Dewey held such a view.

EPISTEMOLOGY: Epistemology deals with knowledge, asking, "How does the mind come to know the nature of reality?" Once again, common sense answers involving what seems to be true may not hold upon closer examination. Words such as "REASON" "FAITH" "PROBLEM SOLVING" "SENSE PERCEPTION" have epistemological connotations. Specifically, the metaphysical idealist would hold that faith determines how we know what the senses cannot determine. A realist would argue that the physical world exists as a matter of common sense. Dr. Johnson, the great 18th Century critic and philosopher stated that he knew darn well the hitching post was there when he banged it with his knee!! For the realist, the universe operates according to fixed laws of nature that the mind is capable of discerning. The skeptic constantly questions. What is true today may be false tomorrow.

AXIOLOGY: We are more familiar with the word ETHICS. Ethical questions ask, "What is good? " What is evil?" "What is beautiful, ugly?" Here the individual is concerned with making value judgments, about the nature of reality and what is worth knowing about it. For a realist, the authority for any action is the word of God made known through Sacred Scripture and revelation. The realist accepts what is reasonable to believe given the norms of the culture. Pope said, "Whatever is is right." The pragmatist argues that whatever solves a problem is correct.

HINTS FOR STUDY:

1. read the material slowly and in small bits more than once. Do not go on if you are confused about a given area.

2. ask plenty of questions.

3. seek additional help from the instructor.

4. don't give up. No one including your instructor learned this immediately or is finished learning it. The study of philosophy is a continuous process.

5. note that the remainder of the course is based on the material in this packet. Each literary period develops the philosophy from the previous one, and all philosophical ideas in this course center on a concept we call THE GREAT CHAIN OF BEING [title of a book by Arthur Lovejoy].

Classical Philosophy

The material in this packet is taken from the following sources/periods:

1. Greek Classical writers: Plato and Aristotle: THE REPUBLIC and THE TIMAEUS

2. Medieval writers influenced by classicism such as Aquinas

3. The above mentioned critic, Arthur Lovejoy (Harvard philosophy professor) whose work The Great Chain of Being is considered one of the most important books in the history of philosophy.

ISSUE ONE: The nature of reality (metaphysics). The philosophy in this packet concerns two important introductory matters: a) the chain of being, and 2) the problem of the one and the many.

PLATO: You have often heard that the greatest thing to learn is the idea of the good by reference to which just things and all the rest become useful and beneficial...The good differs in its nature from everything else in that the being who possesses it always and in all respects has the most perfect sufficiency and is never in need of any other thing.

LOVEJOY: There was plainly implicit in this idea of the good, a strange consequence which was to dominate the religious thought of the west. If by God you meant the being who possesses the good in the highest degree, and if the good meant absolute self-sufficiency,...then the existence of the entire sensible [our world of ordinary sense perception] world in time can bring no addition of excellence to reality.

[What is the obvious problem Lovejoy found in Plato?]

EDITOR COMMENT: The problem Plato raised was recognized by Plato himself: PLATO: the objects of knowledge [in our world of sense perception] not only receive from the presence of the good their being known, but their very existence and essence is derived to them from it.

LOVEJOY'S REACTION: [the above problem]...gave rise to many of the most characteristic internal conflicts. the opposite strains which mark its history--the conception of (at least) Two-Gods-in-One, of a divine completion which was yet not complete in itself, since it could not be itself without the existence of beings other than itself and inherently incomplete; of an Immutability which required, and expressed itself in, Change; of an absolute which was nevertheless not truly absolute because it was related, at least by way of implication and causation to entities that were not its nature and whose existence...were antithetical to its immutable substance.

EDITOR COMMENT: How many beings (the many) should be created by the (one)? PLATO: The sensible counterparts of every one of the ideas. LOVEJOY'S REACTION: The fullness of the realization of conceptual possibility in actuality [sense perception world] is called the principle of plenitude. The implication is that the world of ideas would be deficient without the world of sense perception. For the absolute good to give rise to anything less than the complete world in which the model [the totality of forms or ideas] would be less than the ideal counterpart would be a contradiction.

EDITOR QUESTION: What serious problem concerned Medieval philosophers based on the assumptions discussed so far?...

EDITOR COMMENT (TRANSITION TO ARISTOTLE): Aristotle spoke of creatures giving rise to, in Lovejoy's words, "...a linear series of classes. And such a series tends to show a shading off of the properties of one class into those of the next rather than a sharp-cut distinction between them."

ARISTOTLE: Nature for example passes so gradually from the inanimate to the animate that their continuity renders the boundary between them indistinguishable...Plants come immediately after inanimate things; and plants differ from one another in the degree in which they participate in life. And the transition from plants to animals is continuous; for one might question whether some marine forms are animals or plants, since many of them are attached to the rock and perish if they are separated.

EDITOR COMMENT: Everything except God has some measure of privation or imperfection and the further away from God, the more the privation.

We are reminded by Richard Tarnas (The Passion of the Western Mind, p. 68) of how perfectly art mimes life. Look at Raphael's The School of Athens:

Now observe this closeup:

If Plato is on the left, and Aristotle on the right, what do you notice that shapes the direction of Western philosophy?

(Hint: look at each figure's right arm).

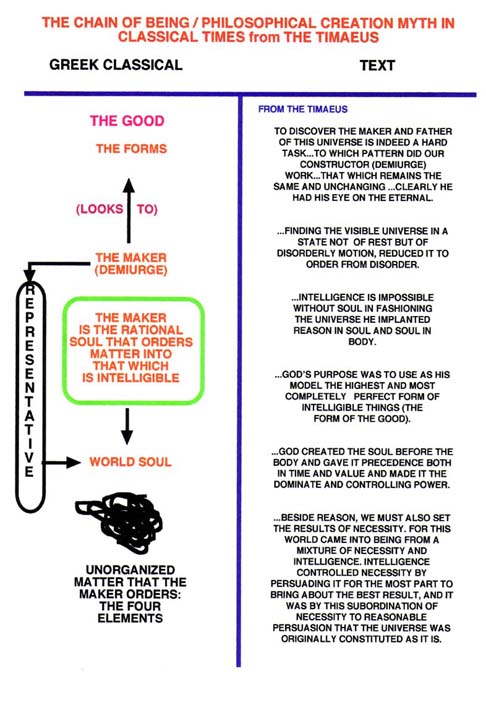

FROM THE TIMAEUS:

Despite the popularity of The Republic, Timaeus was better known in the Middle Ages given how the Medieval church was able to correlate some essential elements with its doctrine. But as you read this selection, note some essential differences. Just as Plato's idea of the Good does not correspond precisely with church teaching, neither does the actions of the Maker here. What are the essential differences and similarities?

Some vocabulary and concepts to define / explain:

The Text:

Timaeus: All men, Socrates, who have any degree of right feeling, at the beginning of every enterprise, whether small or great, always call upon God. And we, too, who are going to discourse of the nature of the universe, how created or how existing without creation, if we be not altogether out of our wits, must invoke the aid of Gods and Goddesses and pray that our words may be acceptable to them and consistent with themselves. Let this, then, be our invocation of the Gods, to which I add an exhortation of myself to speak in such manner as will be most intelligible to you, and will most accord with my own intent.

First then, in my judgment, we must make a distinction and ask, What is that which always is and has no becoming; and what is that which is always becoming and never is? That which is apprehended by intelligence and reason is always in the same state; but that which is conceived by opinion with the help of sensation and without reason, is always in a process of becoming and perishing and never really is. Now everything that becomes or is created must of necessity be created by some cause, for without a cause nothing can be created. The work of the creator, whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect; but when he looks to the created only, and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect. Was the heaven then or the world, whether called by this or by any other more appropriate name-assuming the name, I am asking a question which has to be asked at the beginning of an enquiry about anything-was the world, I say, always in existence and without beginning? or created, and had it a beginning? Created, I reply, being visible and tangible and having a body, and therefore sensible; and all sensible things are apprehended by opinion and sense and are in a process of creation and created. Now that which is created must, as we affirm, of necessity be created by a cause. But the father and maker of all this universe is past finding out; and even if we found him, to tell of him to all men would be impossible. And there is still a question to be asked about him: Which of the patterns had the artificer in view when he made the world-the pattern of the unchangeable, or of that which is created? If the world be indeed fair and the artificer good, it is manifest that he must have looked to that which is eternal; but if what cannot be said without blasphemy is true, then to the created pattern. Every one will see that he must have looked to, the eternal; for the world is the fairest of creations and he is the best of causes. And having been created in this way, the world has been framed in the likeness of that which is apprehended by reason and mind and is unchangeable, and must therefore of necessity, if this is admitted, be a copy of something. Now it is all-important that the beginning of everything should be according to nature. And in speaking of the copy and the original we may assume that words are akin to the matter which they describe; when they relate to the lasting and permanent and intelligible, they ought to be lasting and unalterable, and, as far as their nature allows, irrefutable and immovable-nothing less. But when they express only the copy or likeness and not the eternal things themselves, they need only be likely and analogous to the real words. As being is to becoming, so is truth to belief. If then, Socrates, amid the many opinions about the gods and the generation of the universe, we are not able to give notions which are altogether and in every respect exact and consistent with one another, do not be surprised. Enough, if we adduce probabilities as likely as any others; for we must remember that I who am the speaker, and you who are the judges, are only mortal men, and we ought to accept the tale which is probable and enquire no further.

Socrates: Excellent, Timaeus; and we will do precisely as you bid us. The prelude is charming, and is already accepted by us-may we beg of you to proceed to the strain?

Timaeus: Let me tell you then why the creator made this world of generation. He was good, and the good can never have any jealousy of anything. And being free from jealousy, he desired that all things should be as like himself as they could be. This is in the truest sense the origin of creation and of the world, as we shall do well in believing on the testimony of wise men: God desired that all things should be good and nothing bad, so far as this was attainable. Wherefore also finding the whole visible sphere not at rest, but moving in an irregular and disorderly fashion, out of disorder he brought order, considering that this was in every way better than the other. Now the deeds of the best could never be or have been other than the fairest; and the creator, reflecting on the things which are by nature visible, found that no unintelligent creature taken as a whole was fairer than the intelligent taken as a whole; and that intelligence could not be present in anything which was devoid of soul. For which reason, when he was framing the universe, he put intelligence in soul, and soul in body, that he might be the creator of a work which was by nature fairest and best. Wherefore, using the language of probability, we may say that the world became a living creature truly endowed with soul and intelligence by the providence of God.

THIS PASSAGE HAS BEEN CALLED THE MOST IMPORTANT IN GREEK PHILOSOPHY...WHY?

...BESIDE REASON, WE MUST ALSO SET THE RESULTS OF NECESSITY. FOR THIS WORLD CAME INTO BEING FROM A MIXTURE OF NECESSITY AND INTELLIGENCE. INTELLIGENCE CONTROLLED NECESSITY BY PERSUADING IT FOR THE MOST PART TO BRING ABOUT THE BEST RESULT, AND IT WAS BY THIS SUBORDINATION OF NECESSITY TO REASONABLE PERSUASION THAT THE UNIVERSE WAS ORIGINALLY CONSTITUTED AS IT IS.

NOTE: THE ABOVE IS THE BASIS FOR THE CHAIN OF BEING WHICH FUSED WITH MEDIEVAL CHRISTIANITY:

(Instructor note: The diagram of course is incomplete; just the foundation is presented. As we study Medieval and later Renaissance cosmology, much will be added. You will need to know what the additions are, and why they are necessary.) FOR NOW, AS THE CHURCH EXAMINED THE CLASSICAL SOURCES, WHAT HAD TO BE ADJUSTED?

Influence on Medieval Philosophy

THE FOLLOWING IS AN EXCERPT FROM A LATIN WRITER, AND IT SUMS UP THE DOCTRINE AS TRANSMITTED TO THE MIDDLE AGES:

Since from the supreme God mind arises, and from mind, soul, and since this in turn creates all subsequent things and fills them with all life and since this single radiance illumines all and is reflected in each, as a single face be reflected in many mirrors placed in a series, and since all things follow in continuous succession, degenerating in sequence to the very bottom of the series, the attentive observer will discover a connection of parts from the supreme God down to the last dregs of things, mutually linked together and without a break.

DANTE:

That living light [GOD]

Through his own goodness reunites its rays

In new substance as in a mirror,

Itself eternally remaining one.

Thence it descends to the last potencies,

Downward from act to act becoming such

That only brief contingencies it makes.

EDITOR COMMENT: A very serious question with ethical implications derived from the above is whether God made the best of all possible universes for us? The issue raised is the PROBLEM OF EVIL/ IMPERFECTION:

ABELARD: If we assume that God could make either more or fewer things than he has, we shall say what is derogatory to his goodness. Goodness can produce only what is good. Hence it is the most true argument of Plato whereby the proves that God could not in any wise have made a better world than he has made:

God desired that all things be good and nothing

bad...out of disorder he brought order, con-

sisting that this was in every way better than

the other. Let us suppose the world to be the

very image of that whole...

God neither does nor omits to do anything except for some rational and supremely good reason, even though it be hidden from us, as that other sentence from Plato says, "Whatever is generated is generated from some necessary cause, for nothing comes into being except there be some due cause and reason antecedent to it." To such a degree is God in all that he does mindful of the good.

It is not to be doubted that all things, both good and bad, proceed from a perfectly ordered plan [the chain of being]. Thus Augustine: Since God is good, evils would not be unless it were a good that there should be evils. As a picture is often more beautiful...if some colors in themselves ugly are included in it, that it would be if it were uniform and of a single color, so from a mixture of evils the universe is rendered more beautiful and worthy.

ST. THOMAS AQUINAS: Now that the essence [God's divine perfectness] is not augmentable or multipliable in itself but can be multiplied only in its likeness which is shared by many. God therefore wills things to be multiplied in as much as he wills and loves his own perfection...all things in a certain manner preexist in God by their types [rationes]. God therefore in willing himself wills other things. The best thing in creation is the perfection of the universe, which consists in the orderly variety of things...thus the diversity of creatures does not arise from diversity of merits, but was primarily intended by the prime agent [God].

AQUINAS' SUMMA THEOLOGICA IS THE SUPREME INTELLECTUAL ACHIEVEMENT OF THE MIDDLE AGES, AND TODAY IS STILL RECOGNIZED AS THE MOST IMPORTANT THEOLOGICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY IN CHURCH HISTORY. HIS FUSION OF ARISTOTLE'S PHILOSOPHY AND CHURCH DOGMA MARKED A TURNING POINT IN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY.

EXAMINE HIS ARGUMENTS FOR THE EXISTENCE OF GOD. THESE ARE BASED ON ARISTOTLE'S LAWS OF CAUSALITY...

Material cause--the wood

Formal cause--the idea of the table

Efficient cause--the maker of the table

Final cause--the purpose for which the table was made

FORMAL LOGIC[ THE SYLLOGISM] WAS ALSO USED BY ARISTOTLE AS PART OF A PEDAGOGICAL METHOD KNOWN IN THE MEDIEVAL UNIVERSITIES AS SCHOLASTICISM:

Major premise: All men are mortal

Minor premise: John is a man

Conclusion: John is mortal

The practice, however, was far more complicated as the following excerpt from a Medieval textbook illustrates. There are two participants, an ASSAILANT and a DEFENDER. The assailant has offered the following argument: The procedure is deductive...

MP: No world independent of consciousness exists

MP: An external world is a world independent of consciousness

CONCL.: An external world does not exist

The defender responds:

At the major premise, I take a distinction. No world independent of all consciousness? I waive the question. No world independent of my consciousness? I deny it.

At the minor premise, I counter-distinguish. Of all consciousness? I deny it. Of my consciousness? I grant that....

WE WILL STUDY IN THE RENAISSANCE, REACTIONS AGAINST THIS METHOD WHEN WE CONSIDER BACON'S INDUCTION.

from the Summa Theologica

First Part

Question 2

Article 3

Whether God exists?

Objection 1. It seems that God does not exist; because if one of two contraries be infinite, the other would be altogether destroyed. But the word "God" means that He is infinite goodness. If, therefore, God existed, there would be no evil discoverable; but there is evil in the world. Therefore God does not exist.

Objection 2. Further, it is superfluous to suppose that what can be accounted for by a few principles has been produced by many. But it seems that everything we see in the world can be accounted for by other principles, supposing God did not exist. For all natural things can be reduced to one principle which is nature; and all voluntary things can be reduced to one principle which is human reason, or will. Therefore there is no need to suppose God's existence.

On the contrary, It is said in the person of God: "I am Who am." (Ex. 3:14)

I answer that, The existence of God can be proved in five ways.

The first and more manifest way is the argument from motion. It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion. Now whatever is in motion is put in motion by another, for nothing can be in motion except it is in potentiality to that towards which it is in motion; whereas as a thing moves inasmuch as it is in act. For motion is nothing else than the reduction of something from potentiality to actuality. But nothing can be reduced from potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality. Thus that which is actually hot, as fire, makes wood, which is potentially hot, to be actually hot, and thereby moves and changes it. Now it is not possible that the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same respect, but only in different respects. For what is actually hot cannot simultaneously be potentially hot; but it is simultaneously potentially cold. It is therefore impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.

The second way is from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is an order of efficient causes. There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several, or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.

The third way is taken from possibility and necessity, and runs thus. We find in nature things that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found to be generated, and to corrupt, and consequently, they are possible to be and not to be. But it is impossible for these always to exist, for that which is possible not to be at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to be, then at one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true, even now there would be nothing in existence, because that which does not exist only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence--which is absurd. Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something the existence of which is necessary. But every necessary thing either has its necessity caused by another, or not. Now it is impossible to go on to infinity in necessary things which have their necessity caused by another, as has been already proved in regard to efficient causes. Therefore we cannot but postulate the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God.

The fourth way is taken from the gradation to be found in things. Among beings there are some more and some less good, true, noble and the like. But "more" and "less" are predicated of different things, according as they resemble in their different ways something which is the maximum, as a thing is said to be hotter according as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest; so that there is something which is truest, something best, something noblest and, consequently, something which is uttermost being; for those things that are greatest in truth are greatest in being, as it is written in Metaph. ii. Now the maximum in any genus is the cause of all in that genus; as fire, which is the maximum heat, is the cause of all hot things. Therefore there must also be something which is to all beings the cause of their being, goodness, and every other perfection; and this we call God.

The fifth way is taken from the governance of the world. We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result. Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly,

do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer. Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.

Reply to Objection 1. As Augustine says (Enchiridion xi): "Since God is the highest good, He would not allow any evil to exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil." This is part of the infinite goodness of God, that He should allow evil to

exist, and out of it produce good.

Reply to Objection 2. Since nature works for a determinate end under the direction of a higher agent, whatever is done by nature must needs be traced back to God, as to its first cause. So also whatever is done voluntarily must also be traced back to some higher cause other than human reason or will, since these can change or fail; for all things that are changeable and capable of defect must be traced back to an immovable and self-necessary first principle, as was shown in the body of the Article.

Translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Copyright © 1947 Benzinger Brothers Inc., Hypertext Version Copyright © 1995, 1996 New Advent Inc.

PROBLEM OF EVIL'S CAUSES:

1. cannot be God

2. can be metaphysical evil

3. can be bad choices--disruption of the chain

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||